A Divine Queer Icon from Roman Bocholtz

Author: Christian Kicken

Photography: Provinciaal Depot Limburg, Metropolitan Museum, Prado Museum en Museum of Classical Archaeology Cambridge

In the coming months, the travelling exhibition “Roman Villas in Limburg” can be seen at the pop-up location of the Roman Museum in Heerlen. A handsome curly-haired young man graces the exhibition’s promotional material. After a sensational discovery in the soil of Bocholtz, this bronze lad slowly faded into the museum background—but now he’s back in the spotlight. Who is this mysterious poster boy?

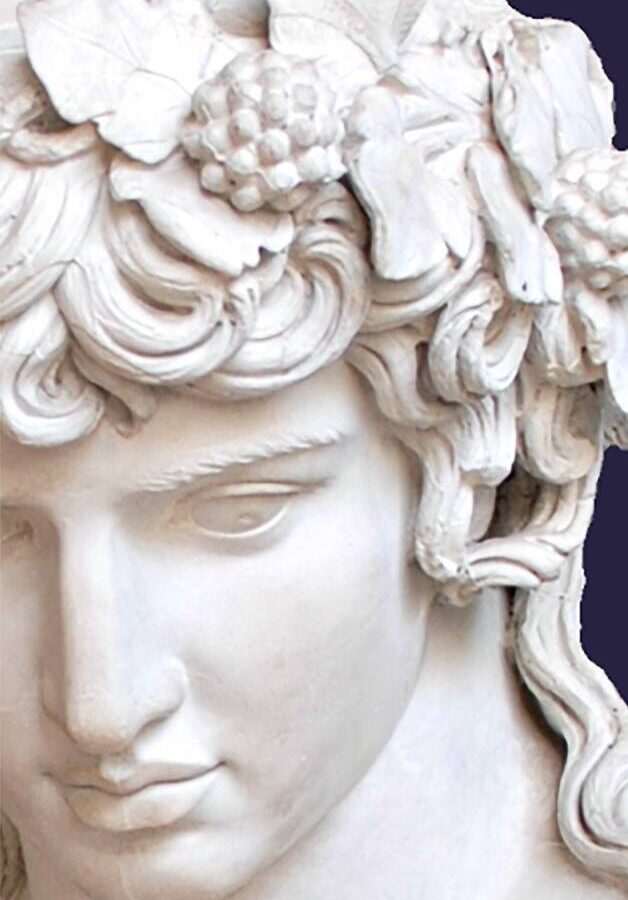

Bust Balsamarium

In October 2003, farmer Hupperetz from the border village of Bocholtz discovered a strange stone in his field. His plough had hit a Roman-period cinerary chest containing the cremated remains of a deceased man. The man, aged 20 to 34, was likely a wealthy owner or resident of the nearby Villa Vlengendaal, an agricultural estate whose characteristic residence was already discovered in 1910. Archaeologists also found traces of the grave monument. After the funeral, the cinerary chest, along with a large number of grave goods, had been placed in a wooden burial chamber and covered with a burial mound, a tumulus. Among the items given to the deceased was a bust-shaped balsamarium: a costly oil or ointment flask with a handle and little lid, usually in the form of a human figure. In Roman times, such pieces were used especially for showing off in public bathhouses. Bust-shaped balsamaria typically appear in elite burials; a comparable example was found in one of the rich graves on the Kollenberg at Esch (North Brabant).

Photo: Bronze balsamarium (16 cm high) from Bocholtz. Collection and image: Provincial Depot for Archaeological Finds Limburg.

Sign of a God

After its discovery, the Bocholtz balsamarium was on view for a long time in permanent exhibitions in Heerlen and Leiden. Those displays did not fully explain how complex it is to identify the young man represented. Fans of mythology can quickly recognize him by the striking garment over his left shoulder: an animal skin, an attribute of the well-known god Bacchus—called Dionysus by the ancient Greeks. As a deity, he presided over wine, ecstasy, and much more. That might seem to settle it, but there is another candidate.

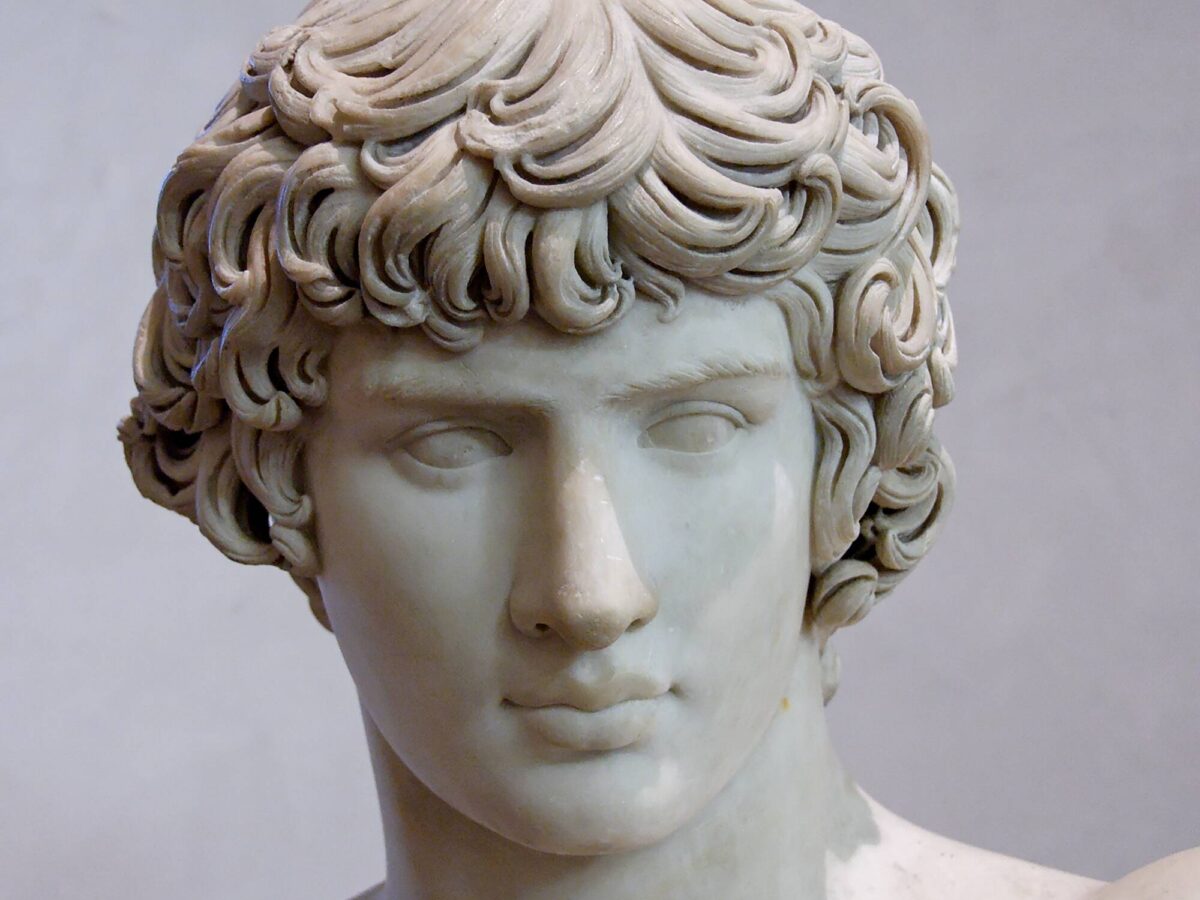

Photo: Marble statue of Bacchus (Dionysus) with animal skin. Collection and image: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Made into a God

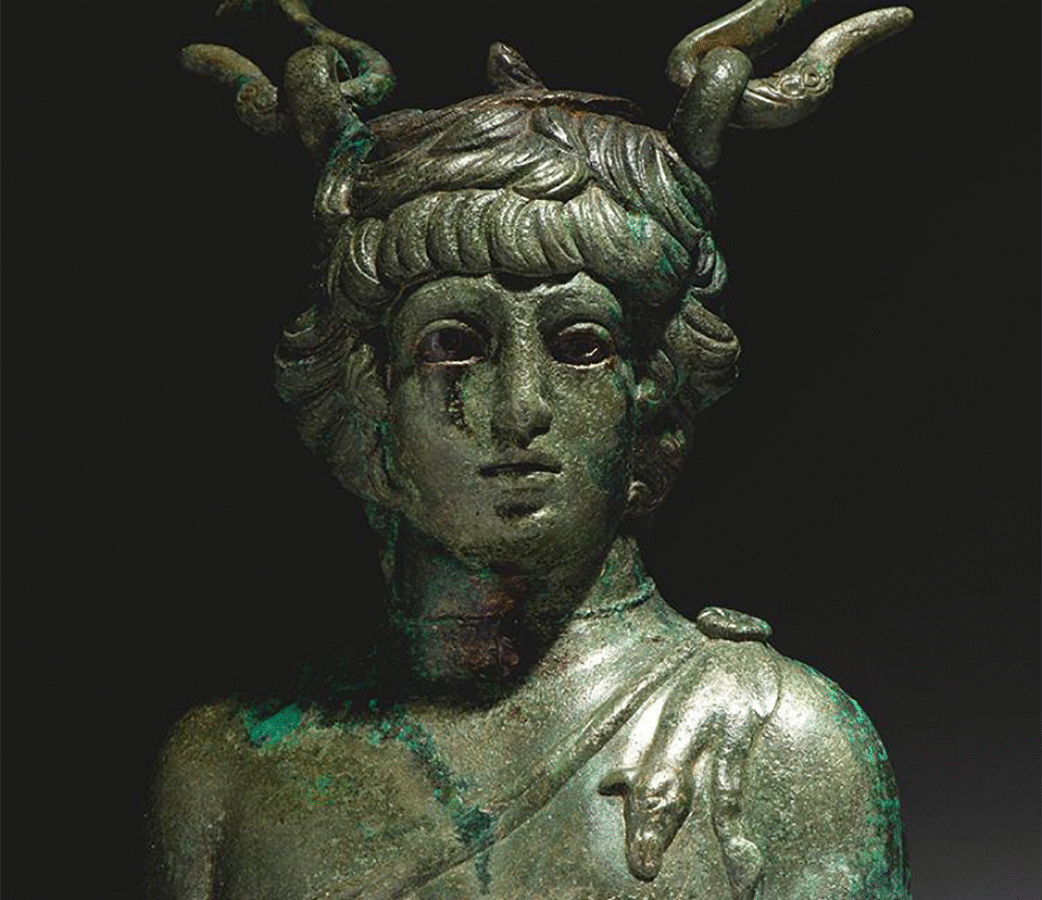

Experts in Roman (art) history see someone else in the bust: the historical figure Antinous. This teenager from ancient northwestern Turkey (the province of Bithynia) was the favourite and lover of Emperor Hadrian (AD 76–138). According to Roman norms, the ruler was married to Empress Vibia Sabina, but it was tolerated for Roman men to have (sexual) relationships with other men provided a certain hierarchy was observed. Today Hadrian and Antinous are often regarded as romantic partners, especially because of the emperor’s reaction after Antinous’s sudden death in AD 130.

A grief-stricken Hadrian immediately declared his beloved a new deity and had him worshipped in the new city of Antinoöpolis—“City of Antinous.” To keep the young man’s memory alive throughout the empire, the emperor popularised Antinous’s portrait, whose face then served as the model for various images of ancient gods such as Bacchus, Apollo, Osiris, or the lesser-known woodland god Silvanus. One result of this imperial craze also reached the villa at Bocholtz.

Photo: Marble head of Antinous. Collection: Prado Museum, Madrid; image: Wikimedia Commons.

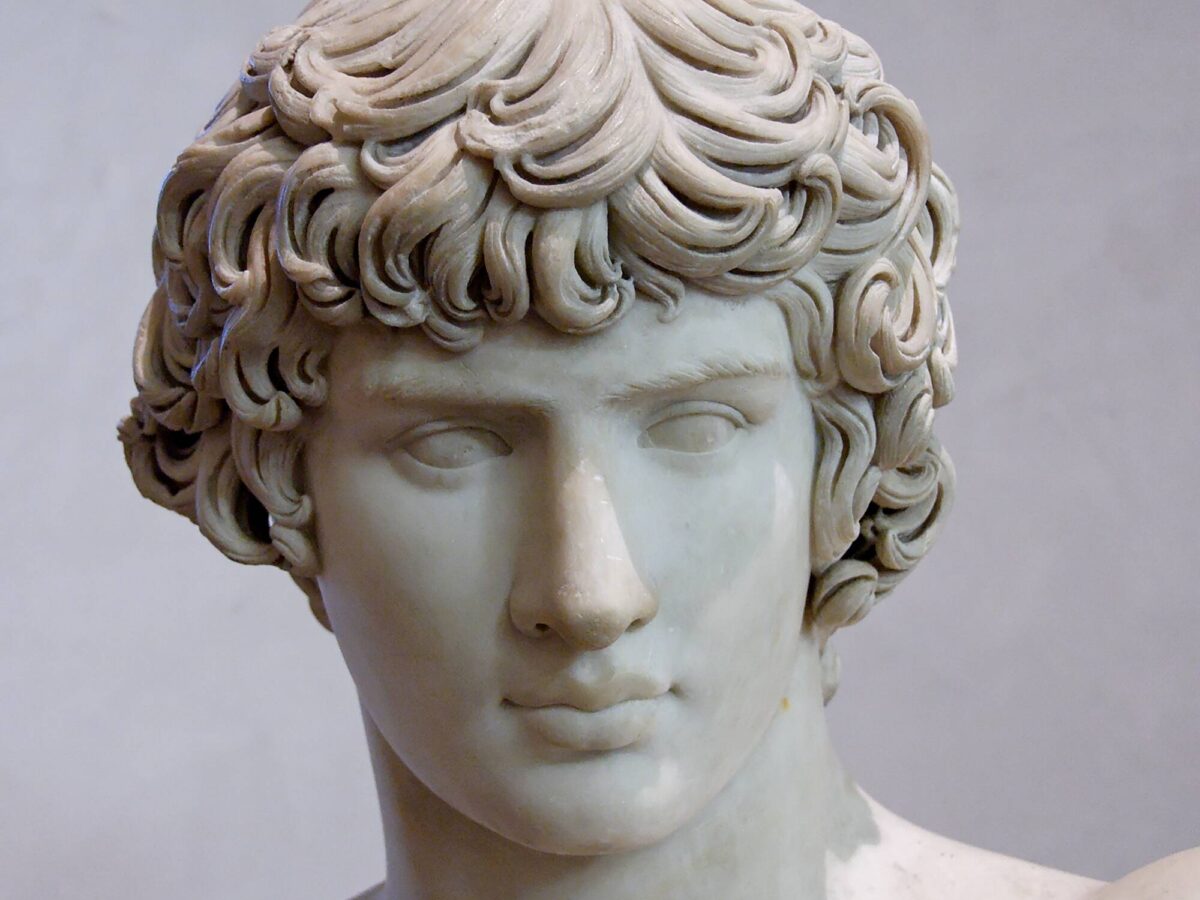

‘Who is this diva?’

The global queer community is increasingly calling attention to the histories of gender and sexuality, and embraces Antinous ever more strongly as a historical queer icon. The striking balsamarium was a cherished possession of the deceased owner—but did he also recognize the famous Antinous in the little flask? A maker in Egypt or Gaul likely produced the object in the 130s or 140s, fully aware of the young man who served as its model.

By various routes, the flask found its way to Roman Bocholtz, to a man who died around AD 175–200. If his grave goods reflect his interests, this literate man had a taste for hunting, bathing, and feasting. He himself would most likely have recognized the god Bacchus in this showpiece—fitting his luxurious lifestyle. How, then, should we best view this masterpiece from Roman Netherlands? As a flask in the form of the immortal Bacchus, after the likeness of the mortal Antinous. Or can one call the latter immortal after all? This balsamarium keeps his memory alive.

Photo: Portrait of Antinous on a poster for a “Queer Antiquities Trail.” Image: The Museum of Classical Archaeology, Cambridge.