Roman Aachen Thrived Thanks to Emperor Trajan

Author: Harry Lindelauf

Photography: Stad Aken, Wiki Commons, Pinakothek München, Harry Lindelauf

The idea that Roman Aachen consisted only of thermal baths and a few houses can be thrown out the window. In TripAdvisor terms, it was number six among the 36 major settlements of Lower Germania. The discovery of castellum foundations near the Pont Tor at the Market Square in April 2024 confirmed that status.

City archaeologist Andreas Schaub of Aachen is convinced of the regional importance of Roman Aachen. His view is based on numerous recent findings and new analyses of older discoveries.

The story of Roman Aachen begins around the start of the first century. The healing, sulfur-rich waters (reaching up to 72°C) were seen by the Romans as a blessing for their sophisticated bathing culture. They built their first bathhouse at the thermal “Quirinus” spring.

Schaub notes a remarkable fact: whereas Roman buildings elsewhere began as wooden structures, Aachen’s earliest constructions were built of stone, with plastered walls and tiled roofs. The settlement began to flourish — but the real breakthrough came in the year 98 CE. Marcus Ulpius Trajanus (53–117), then governor of Lower Germania based in Cologne, was appointed emperor. He did not depart for Rome until the following year. During that year, he shared his vision for the province’s structure with local authorities.

Photo: Emperor Marcus Trajanus (reigned 98–117 CE). The bust is in the Glyptothek in Munich. (Wikimedia Commons)

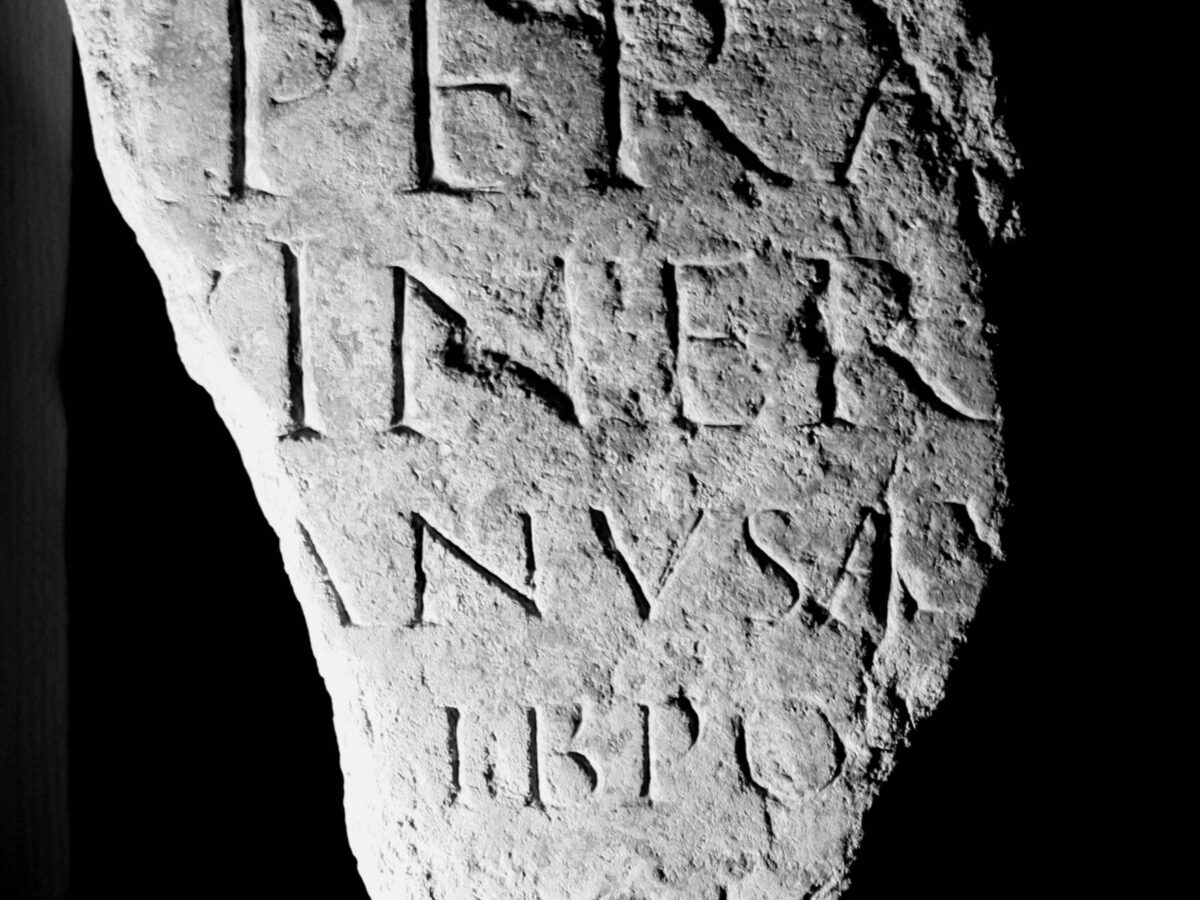

A Commemorative Stone

After his departure, Trajan’s vision was implemented. Across the province, the Romans reorganised administration, frontier defence, and large-scale agriculture. Aachen was one of the cities Trajan wanted to expand — and there is proof of his involvement.

An inscription on a commemorative stone names Trajan as the patron of public construction projects in the city. The stone was found in the debris of a public building near the forum. This forum was part of a coordinated architectural project featuring two colonnades and a large basilica — a grand administrative complex representing imperial authority from Cologne.

Photo: Inscription mentioning Emperor Trajan as patron of construction works.

Aqueduct and Expansion

At that time, the city had two major thermal baths supplied by the Kaiserquelle and the Quirinusquelle. There were both public baths and smaller, private bathing facilities. The great demand for clean, cool water led the Romans to build a two-kilometre-long aqueduct from Burtscheid in the south. Unlike the typical Roman aqueducts with arches, the Aachen version ran mostly underground. Its endpoint was a large reservoir, remains of which have been discovered.

Under Trajan’s influence, Aachen grew rapidly in the early 2nd century to an area of about 30 hectares. Around the bustling centre lay large residential and workshop districts. At that time, the population was between 2,000 and 3,000 inhabitants.

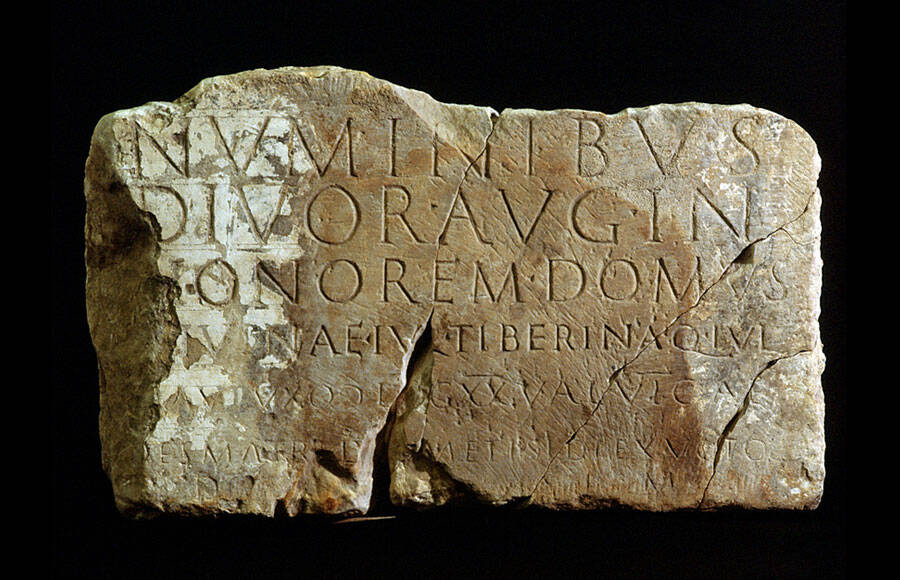

Between the Roer, Meuse, Geul and Ourthe

Schaub explains: “Thanks to the Trajan inscription, we know that there was a construction project to which he wanted to attach his imperial name. That clearly wasn’t a doghouse — we are undoubtedly talking about the forum. From this, it follows that Aachen had an administrative and governmental role.”

Additional evidence of Aachen’s regional importance comes from ten altar stones found near the forum, dedicated by officials of the provincial governor. One of them bears the name Julius Severus, who served as provincial administrator between 142 and 151 CE. According to Schaub, these finds confirm that the region between the Roer, Meuse, Geul, and Ourthe rivers was governed from Aachen.

Photo: Altar stone from Aachen dedicated by Julia Tiberina, wife of centurion Quintus Julius Flavius. (City of Aachen)

Destruction and Reconstruction

Around 272 CE, disaster struck: after a series of raids, Frankish tribes burned Roman settlements west of the Rhine — Aachen among them. Archaeologists have found traces of a massive fire. The Romans needed until about 330 CE to recover.

They built a fort (castellum) roughly where the present-day Market Square lies. In April 2024, remains of one of its gates were discovered on the Pontstraße — a 5.3-metre-wide foundation that may once have supported an imposing wall up to eight metres high. Earlier excavations at the Market Square had already uncovered parts of the castellum wall and a round tower. The Roman period in Aachen lasted at least until the 5th century, though its precise end remains uncertain.

“Superlative” Discoveries

Much of today’s knowledge about Roman Aachen is thanks to a major sewer replacement project in the city centre, replacing pipes dating from 1890. Schaub remarks: “It advanced our understanding of Roman Aachen by miles. I can’t even think of a ‘superlative’ strong enough to describe it.”

The tunnelling allowed archaeologists to access ancient layers, in some places reaching the Roman habitation level, now located 3.5 to 7 metres below the surface. All findings have been meticulously documented — filling two entire archive cabinets.

Photo: Andreas Schaub — “It advanced our knowledge of Roman Aachen by miles; I can’t think of a ‘superlative’ strong enough.”

Aquae Granni?

What does Andreas Schaub still hope to discover?

He gives two answers to one question: “Where are the cemeteries? At the Königshügel, we found a small early medieval burial site where people were already being buried at the end of the Roman period. But during the Roman centuries, thousands must have lived — and died — here. Graves and tombstones are invaluable sources: Who were these people? Where did they come from?”

“And secondly, I would love to find the Roman name of Aachen in a contemporary text. Medieval writers called it Aquae Granni. It sounds plausible — but I’d like to be sure.”

There is a small chance of an answer. Beneath the Market Square, in the foundation of the castellum, lie three fragments of a milestone — but the visible sides are blank. If there is any inscription, it would be on the embedded side, unlikely ever to be seen. Still, as Schaub says, “where there’s hope…”

Photo: Map of Roman remains in central Aachen. The green circle marks the castellum wall, including the Market Square near today’s Town Hall.