Square Will Soon Refer to Coriovallum’s Aqueduct

Author: Harry Lindelauf

Photography: Het Romeins Museum, RCE en RMO

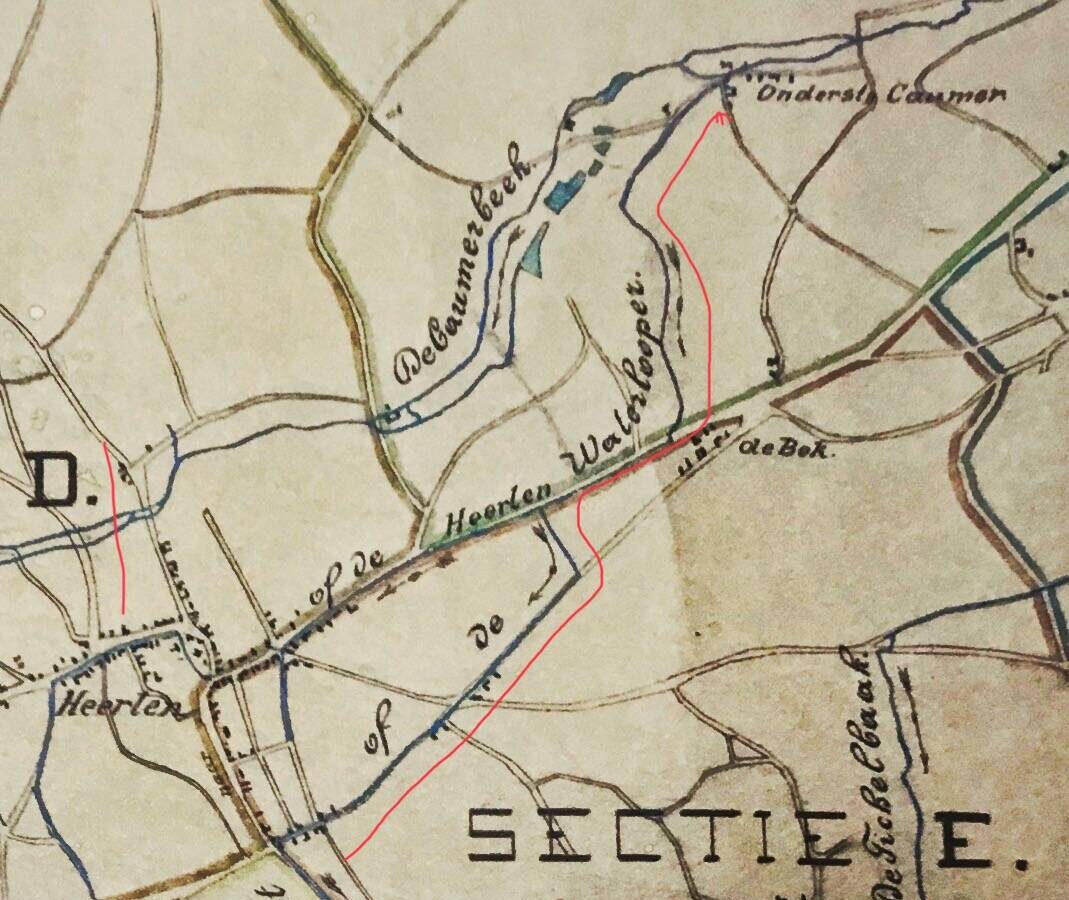

The renewed Raadhuisplein in Heerlen will feature a water channel symbolising the ancient aqueduct of Coriovallum. The Romans once built a water supply system from the upper course of the Caumerbeek stream to the thermal baths. Remarkably, the city continued to draw water from the Caumerbeek until the late 19th century.

Coriovallum (Heerlen) emerged around the beginning of our era, at the crossroads of the Via Belgica and the Via Traiana — a strategically important site. A settlement with trade and crafts soon developed, and by 63 CE, the Romans deemed it time to build a bathhouse.

The site’s strategic location had one major drawback: water had to be drawn from wells 3.5 to 10 metres deep. To the east and west lay the Caumerbeek and the Geleenbeek, but both streams were significantly lower than the inhabited plateau.

Photo: The bathhouse was significantly expanded around the year 96 CE.

A Wooden-Planked Channel

The Romans found a clever solution. About two kilometres away, they located the sources of the Caumerbeek, lying 15 metres higher than the settlement. This natural gradient allowed water to flow by gravity to the bathhouse, homes, and pottery workshops. Thus, they built an aqueduct approximately two kilometres long. It was not a grand series of arches like those seen in southern Europe. The exact design remains unknown, but it was likely an open channel lined with wooden planks.

Photo: Locally found ceramic pipes that fit together — possibly used for rainwater drainage.

The Caumerbeek Made Coriovallum Possible

Today, the Caumerbeek’s sources produce between 18,000 and 68,000 litres of water per hour. If that was also the case in Roman times, there was ample water to supply both the bathhouse and the original course of the stream.

The diversion likely began with a collection basin and sluice, from which the aqueduct ran toward the southeast wall of the bathhouse. It may have had two branches: one leading east to the village and the potteries, and another westward to the baths. Intriguingly, remains of tanneries have been found beside the bathhouse — another industry that required vast quantities of water.

Photo: After the Roman period, two watercourses remained in use — one along Akerstraat toward Pancratiusplein, and another via Vlotstraat (which owes its name to this waterway) toward today’s Kruisstraat.

Enormous Water Consumption

Inside the bathhouse, water was collected in a reservoir and distributed to the various baths, basins, drinking fountains, ornamental fountains, and the large boiler for hot water. The Romans cleverly used the difference in elevation between the south and north walls to maintain pressure and flow.

The water consumption of the 500-square-metre complex was enormous. Each indoor bath held about 5,000 litres, while the outdoor pool contained roughly 58,000 litres. These pools were continuously supplied with fresh water during operation.

Nothing has been found of the aqueduct, as previously mentioned.

Photo: Artist’s impression of the hot-water bath in the bathhouse.

Drainage to the Geleenbeek

What has been found: the drainage channel of the bathhouse.

The gutter, built of natural stone and lime mortar, is now open in the museum, but in Roman times it was covered with stone slabs.

The channel led from the bathhouse southwards, then turned west into what is now Coriovallumstraat.

A few hundred metres further, it emptied into the Geleenbeek at the point where the Via Belgica from Maastricht reached Heerlen.

When the paving of Coriovallumstraat was replaced a few years ago, a central rain gutter was placed in the new pavement to recall the bathhouse drainage.

Photo: A piece of lead drainage pipe with a flange, found on the site of the bathhouse.

Romans Leave, Watercourse Remains

After the departure of the Romans and the end of the bathhouse, the inhabitants continued to use water from a sluice in the Caumerbeek.

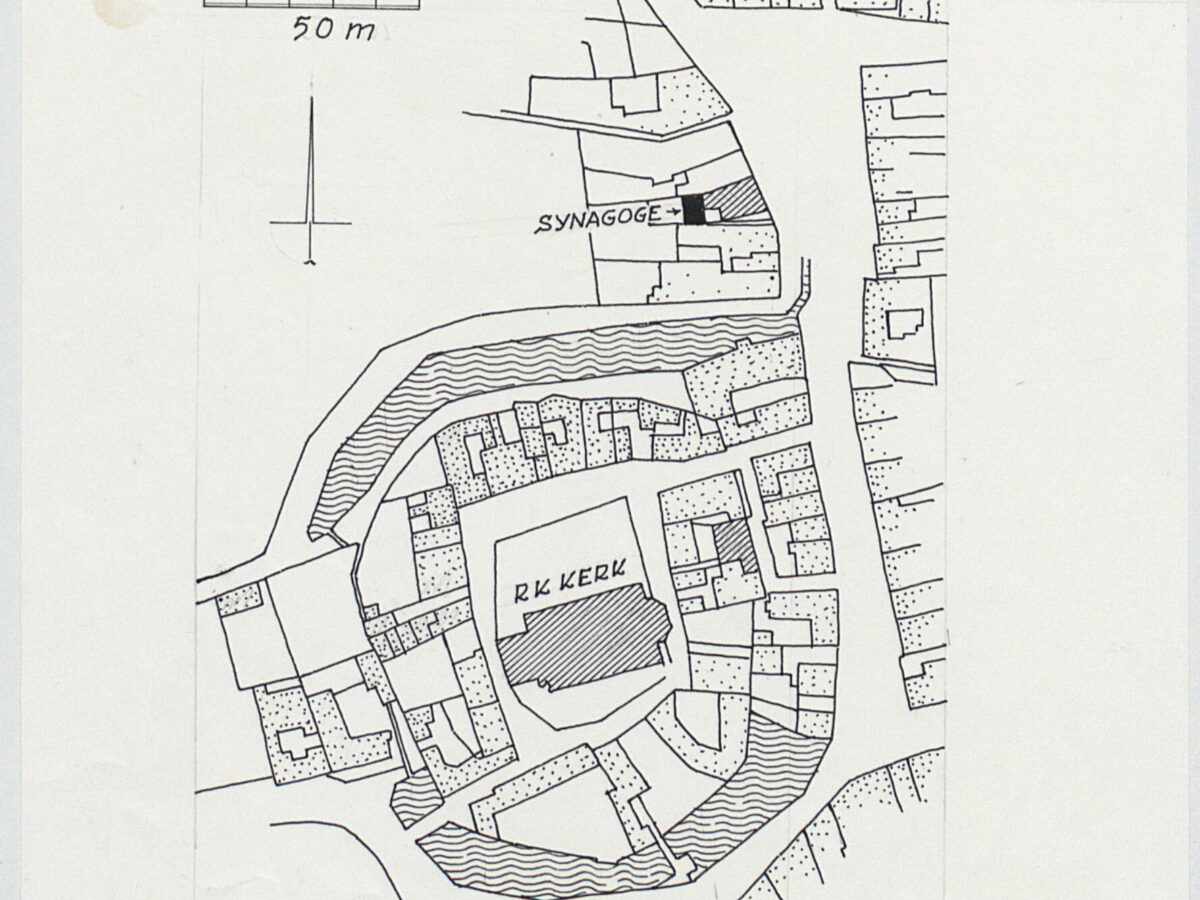

Without water, there is no life — and that takes on another meaning: after the construction of the fortress on the site of today’s Pancratius Church, the water from the Caumerbeek branch was used to fill the moats around the fort. The Romans showed the way, and later inhabitants gladly followed it. The watercourse was now called De Vlotten, and it remained in use until the end of the 19th century. Maps show that two watercourses were dug: one along Akerstraat toward Pancratiusplein, and another via Vlotstraat (yes, hence the street name) toward the present Kruisstraat.

Minutes of a city council meeting from 1819 show that the Caumerbeek did not supply all its water to the city: the original bed with its water mills received water during the week, while the city watercourses had water on weekends. With the arrival of a water supply system in the city, the need for Caumerbeek water disappeared, and De Vlotten vanished.

Photo: Map from 1825 of the site of the fortress with the remaining moats.

In the series of articles about aqueducts along the Via Belgica, earlier editions covered Cologne and Tongeren.

Timeline Coriovallum

± 20 BC to 100 Construction of the Via Belgica.

Year 0 – 50 Construction of the Via Traiana.

Year 0 – 100 Building of wooden houses and military quarters.

Year 65 – 73 Construction of the first bathhouse, 560 m².

Year 100 – 200 Building of stone houses.

± Year 98 Expansion of the bathhouse to 2,500 m².

Year 250 – 300 Construction of a defensive ditch and wall around the bathhouse,

internal reconstruction.

± Year 476 End of Roman authority and use of the bathhouse.

"The flowing water called Vlot, which runs off at certain times from the Caumerbaak, from the Erk standing there in Caumer into the ponds and water conduits in the village of Heerlen, shall, as has been customary from ancient times, during the whole year, and insofar as freezing in winter does not hinder the flow, run every week from Saturday clock noon to Sunday clock noon, for which purpose the said Erk shall be closed by the Administration every Saturday at eleven o’clock in the morning and shall be opened on Sunday."—