Via Belgica follows the route of Caesar’s highway

Author: Harry Lindelauf

Photography: Tom Buijtendorp, Uitgeverij WBooks, Vaticaans Museum, Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Maja d’Hollosy

Gaius Julius Caesar is, more than 2,000 years after his death, once again in the spotlight thanks to an exhibition in Amsterdam and a new book by Tom Buijtendorp. He makes it plausible that Caesar followed the route of the later Via Belgica and renews our image of Caesar — literally and figuratively.

It was the publisher who came up with the idea of accompanying the exhibition at the H’ART Museum (see box) with a route guide. Not yet another book about the emperor, but one that presents Caesar himself and his campaigns in the Low Countries. Archaeologist and author Tom Buijtendorp got to work: “I approach Caesar as the first explorer of the region, which makes you see him differently while walking. Thanks to recent discoveries, there is much more to see than before.”

Beautiful surroundings

He and his wife put on their walking shoes: “I think I walked for about fourteen days for this book.” The collaboration between the non-walker and his wife (a non-Roman) produced a special result. “The routes are interesting for anyone who has an interest in Roman history. And if you have no interest in the Romans, you can still enjoy beautiful walks, because apparently Caesar had an eye for a beautiful landscape,” says Tom Buijtendorp, laughing.

Caesar’s highway

Tom Buijtendorp has literally mapped Caesar’s campaigns from the Roman winter camp in Amiens to the Low Countries. Buijtendorp makes it plausible that Caesar was clever enough to avoid the difficult and dangerous Eifel and Ardennes. He could do so by travelling from east to west along the route where, a few decades later, the Via Belgica was constructed. He calls it Caesar’s highway from the Rhine to the coast near Boulogne — a fast connection with only two major rivers to cross: the Meuse and the Scheldt.

The crossing of the Meuse — you guessed it — lies in Maastricht. Caesar could probably wade through the river thanks to a low water level and accessible banks. It is also possible that he built a temporary bridge.

Roman camp at Caestert

Caesar suffered his greatest defeat of the Gallic War at a hillfort. That was against the Eburones, who lived near Maastricht and Tongeren. Tom Buijtendorp takes the reader to the plateau of Caestert near Maastricht, which contains the only preserved hillfort in the region. Although it has not been proven that the battle took place there, he considers it the most plausible location. The hillfort and the Jeker Valley form, in any case, a perfect setting to bring the battle to life while walking. If it did not happen exactly there, it must have been in a similar environment.

In his book, he uses a “dot score” that quickly shows whether a place is the “most plausible” or perhaps only scores a “maybe.” “Caestert!” is therefore Tom Buijtendorp’s answer to the question of what he would most like to research further. “But so far, only large excavations elsewhere have produced tangible traces of Caesar’s army, and large-scale digging is impossible in this protected area. The Jeker Valley keeps its secrets.”

Our image of Caesar

Based on his earlier research, a facial reconstruction of Caesar was made in wax-like material, partly based on a relatively unknown marble statue in the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden. The book shows recently published contemporary depictions of Caesar that correspond with both the reconstruction and the statue from Leiden. Both were therefore given a prominent place in the book and the exhibition.

According to Buijtendorp, uncertainties remain, but at least it has become clear that for centuries we have been deceived by Roman propaganda.

After his death, Caesar was worshipped in Rome as a god, and the images made in the centuries that followed acquired an ever higher degree of propaganda.

The medal has two sides, as Tom Buijtendorp also makes clear. On the one hand, there is the incense for the successful political and military strategist, the commander who stands among his troops and who, as adventurer and explorer, conquers Gaul and dares to go further north into the heart of the Netherlands. Even the sea does not stop him — in the late summer of 55 BC, he crosses over to England.

Sword and dagger

The reverse side is impressively negative: Caesar seeks dictatorial power and is a ruthless general with genocide on his record. His campaigns were not without strategic blunders, and his overview of the geography of the Low Countries was limited. But by writing his own account, De Bello Gallico, he showed himself a public relations genius, polishing his weak points until they shone as successes.

One way or another, Caesar is and remains the Roman who lives by the sword and dies by the dagger in 44 BC. The book and exhibition provide ample food for thought for anyone wishing to re-evaluate their own image of Caesar. Or, as Tom Buijtendorp puts it: “The book encourages readers to let go of the old image of Caesar, to look for themselves, and to form their own view.”

Julius Caesar in Amsterdam

The exhibition at the H’ART Museum in Amsterdam tells the life story of Julius Caesar through nearly 150 objects. The exhibition can be seen until Monday, 20 May 2024. H’ART Museum is the new name of the Hermitage Museum.

Photo 1

Tom Buijtendorp: “Thanks to recent discoveries, there is much more to see than not long ago.”

Photo 2

The Jeker Valley: the most likely location of the battle between the Eburones and the Romans.

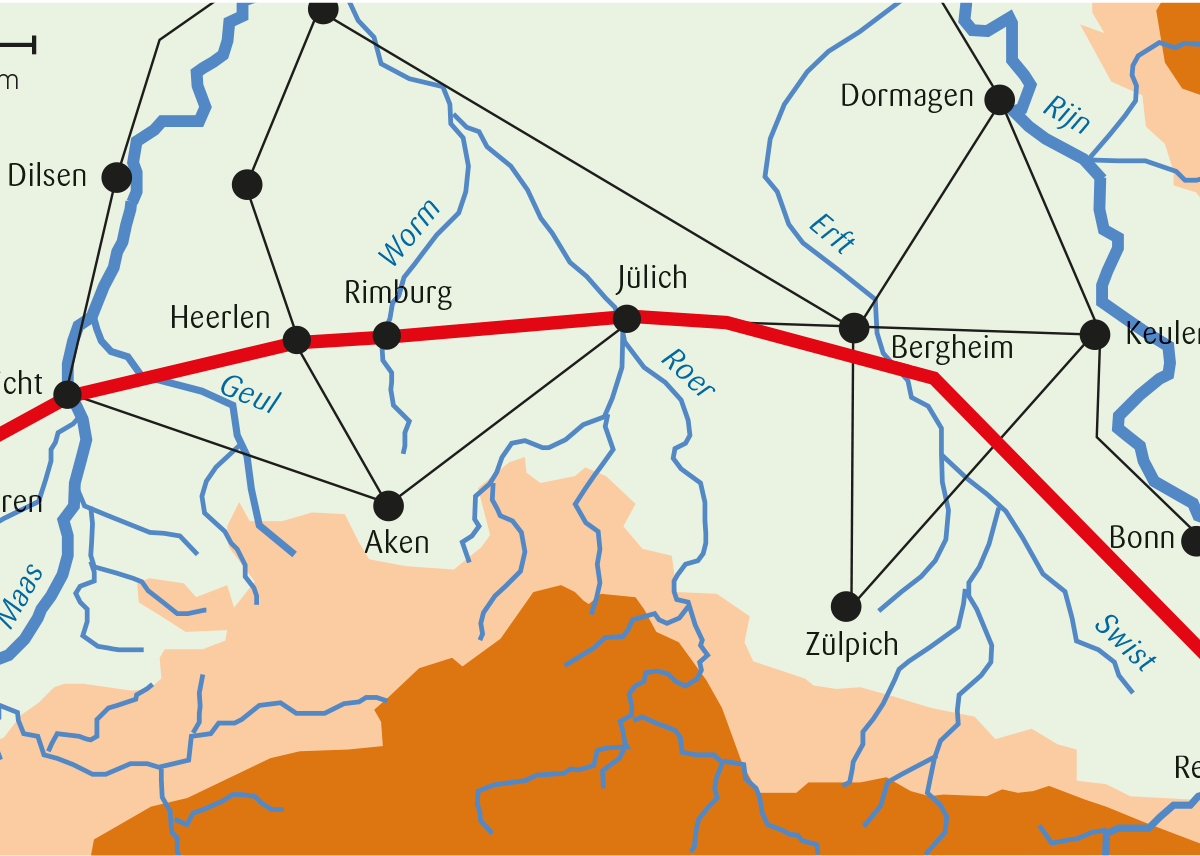

Photo 4

The route that Caesar and his legions most likely followed from Remagen near Koblenz through South Limburg to the west.

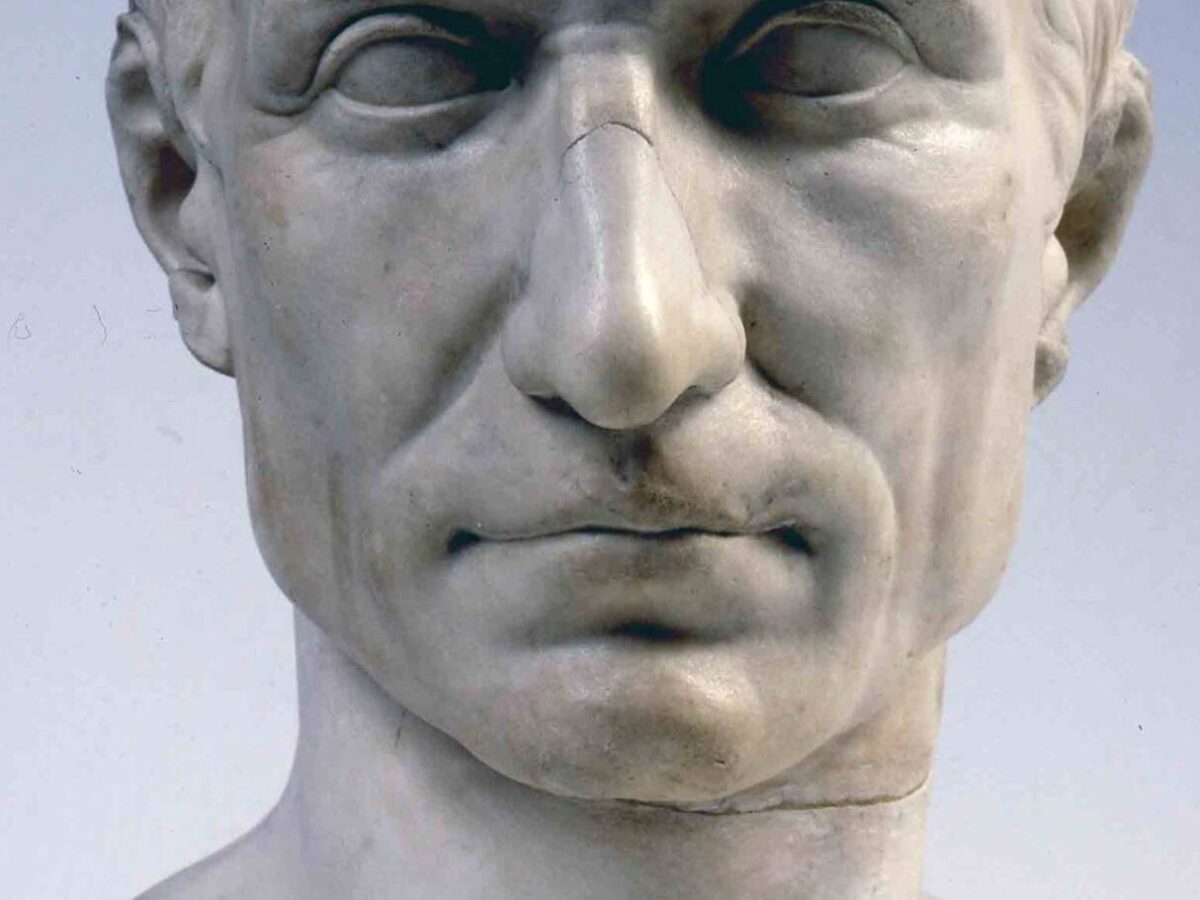

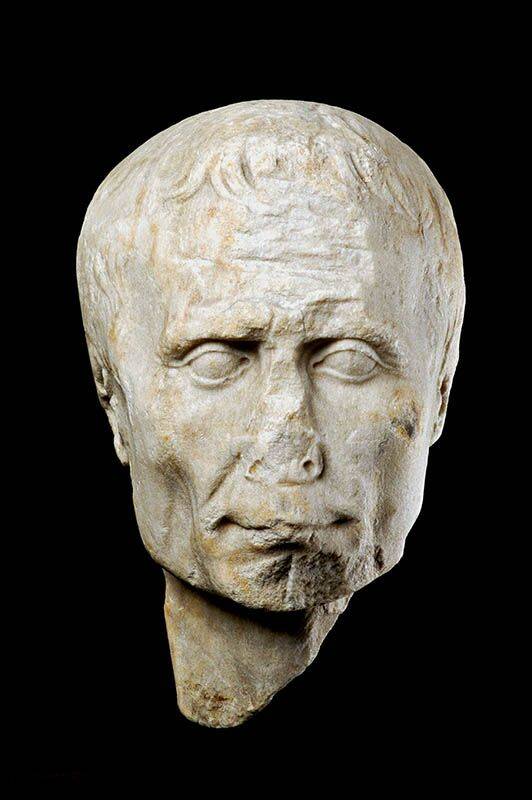

Photo 5

The old image of Caesar: a bust from the Vatican Museums, probably made shortly after his death, and the bust from the collection of the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden.

Photo 6

The Caesar Route, guidebook to Caesar in the Low Countries, published by WBooks.