Innovation through Roman concrete recipe

Author: Harry Lindelauf

Photography: MIT, Thermenmuseum Heerlen, Phillippe Debeerst , L’Oeil Photography/Thermenmuseum, Harry Lindelauf

How can you make concrete that lasts longer and is less harmful to the environment during production? Researchers from the USA and Switzerland searched for this innovation and have now found the solution: it turns out to be a 2,300-year-old recipe for Roman concrete.

Professor Admir Masic of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the USA led the search, with participation from Harvard University and a Swiss materials research institute. Masic found the key in small pieces of concrete from the Roman city wall of Proverno near Rome.

It is known that Roman concrete lasts a very long time: the dome of the Pantheon dates from the year 128. It is also known that another recipe for Roman concrete, thanks to the addition of volcanic ash, hardens under water and even becomes stronger over time. For a long time it was believed that everything about Roman concrete was known.

Photo: the Pantheon in Rome. This version was built around the year 128. The dimensions are impressive: the concrete dome has a diameter of 43.30 metres and is also 43.30 metres high. The opening in the dome has a diameter of nine metres.

Careless concrete

Masic’s team continued and analysed the composition of the piece of concrete from Proverno using the most modern techniques. Masic found it remarkable that Roman concrete contains millimetre-sized pieces of calcium carbonate embedded in a lime-rich material. This had been discovered before but dismissed as the result of careless concrete mixing.

Masic questioned this assumption: “If the Romans put so much effort into creating an extraordinary construction material, following all the detailed recipes that had been improved over many centuries, why would they then take so little care in producing a well-mixed end product?”

Photo: fragment from a waste pit at the Thermenmuseum in Heerlen. A piece of floor with mosaic stones set in pink-coloured concrete.

Quicklime

The team discovered that the mineral fragments are formed when concrete is made with quicklime where normally slaked lime is used. The difference arises from the chemical reaction in the concrete mixture. This reaction releases a great deal of heat, which leads to the formation of the mineral fragments.

Masic also discovered why Roman concrete lasts so long. It turns out that the concrete repairs small cracks by itself. Water that penetrates into the cracks dissolves lime from the pieces of calcium carbonate. That lime crystallises and closes cracks up to 0.5 millimetres wide, as laboratory tests showed. Masic hopes that the research will help reduce the environmental impact of cement production, which currently accounts for about 8 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. The Roman concrete of 2023 should achieve this thanks to a longer lifespan and the development of lighter concrete.

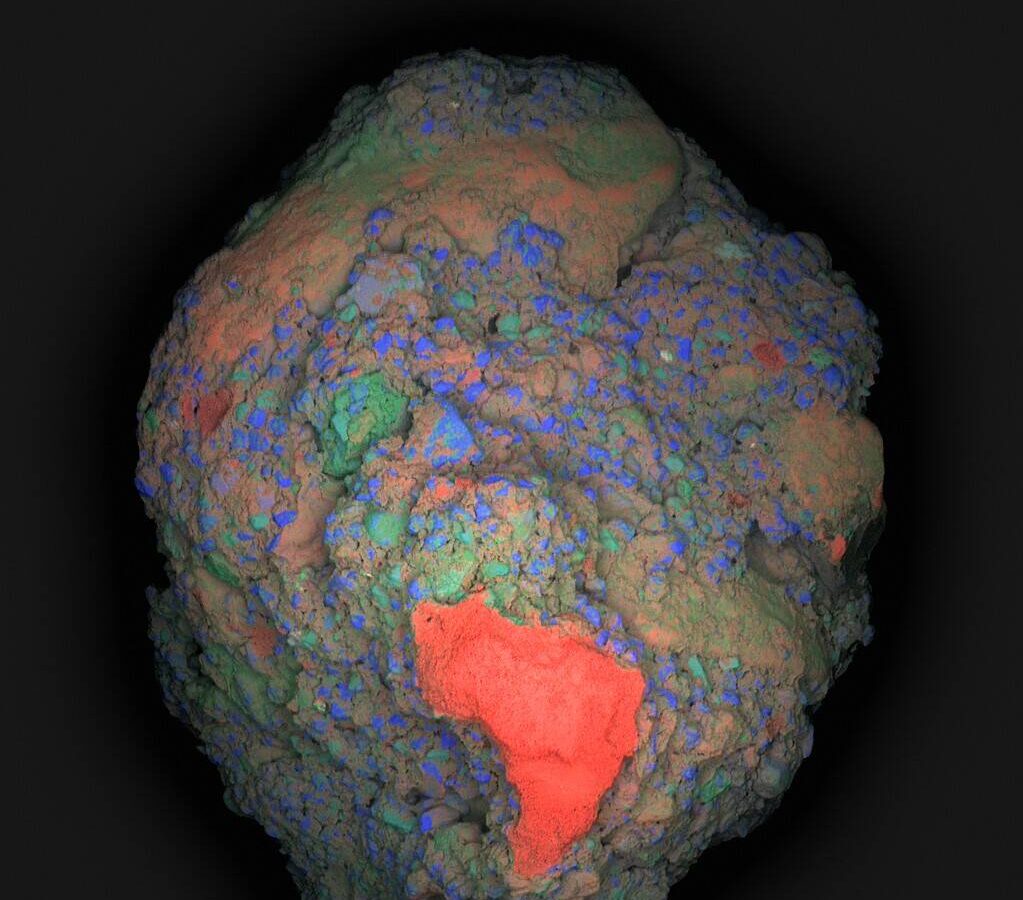

Photo: A piece of concrete. The calcium lights up red, silicon blue and aluminium green. The calcium responsible for the unique self-healing properties is visible in the lower part of the image.

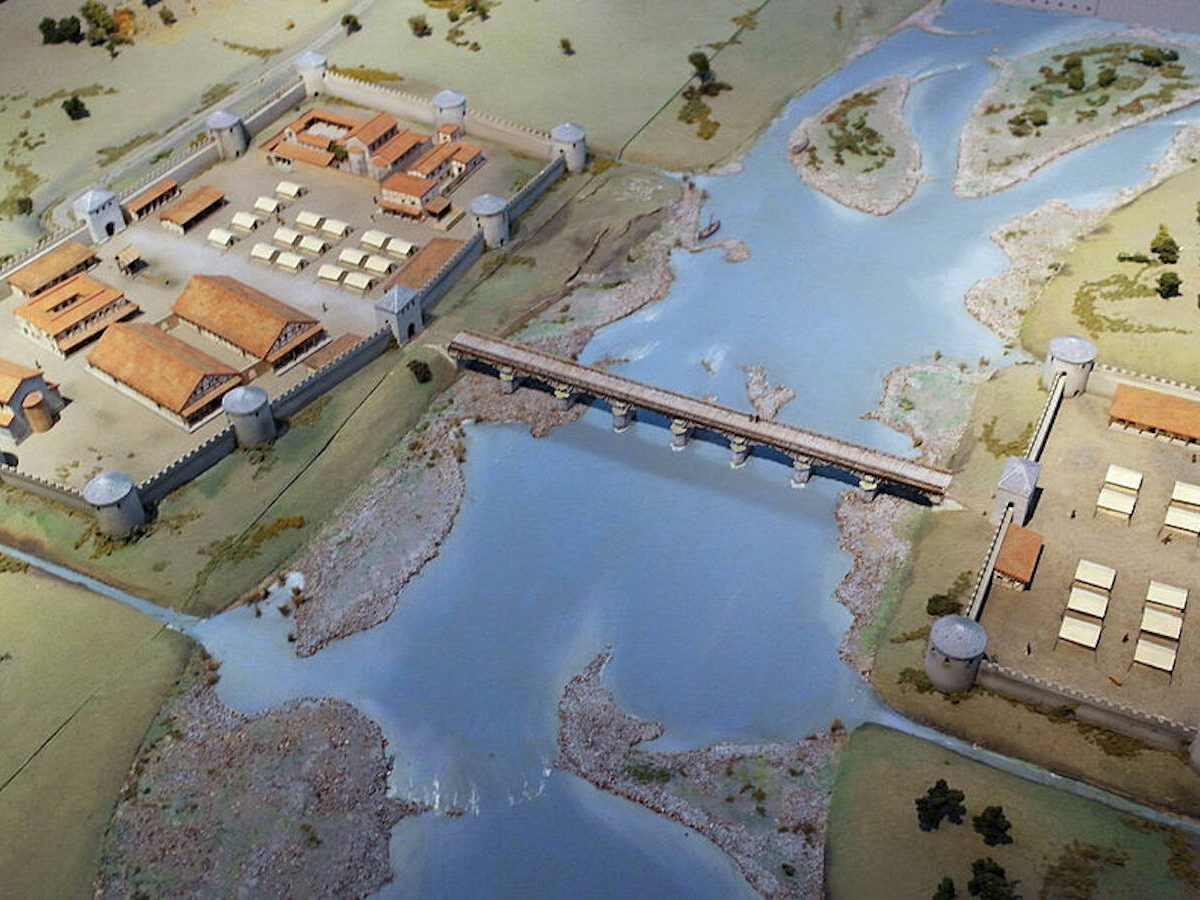

The Pantheon and the Colosseum are two world-famous examples of Roman buildings that could be constructed thanks to Roman concrete. Along the Via Belgica in South Limburg, Roman concrete was used in the construction of the pillars for the Meuse Bridge in Maastricht. For the thermae in Heerlen, too, the Romans worked with concrete, for example as a support layer for a mosaic floor.