Maastricht had not one, but three Roman bridges

Author: Harry Lindelauf

Photography: HCL Fotopersbureau Het Zuiden, HCL Openbare Werken Maastricht, Limburgs Museum, Wikicommons. Video Mergor in Mosam, Harry Lindelauf

The Roman bridge over the Meuse – Maastricht is famous for it. In reality, the Romans built not one but at least three bridges here along the Via Belgica. What remains of these bridges lies underwater and has been a national monument since 2017.

Photo: Roman bridge Maastricht monument (Harry Lindelauf)

Why did the Romans build their Meuse bridges precisely here?

There are several reasons:

- The riverbanks were high enough for access roads and a bridge.

- South of present-day Maastricht the banks were too steep. Further north, the riverbed became so wide that a bridge would have needed to be a kilometre long.

- The wet Jeker delta provided military protection to the south, and the confluence of two rivers had religious significance for the Romans.

- At normal water levels it was possible to cross here even before the Romans arrived.

- The location fitted perfectly into the route of the Roman road from Cologne to Bavay, which Marcus Agrippa had constructed by auxiliary troops shortly before the start of our era.

- The Meuse bridge connected Tongeren and Heerlen with the Roman harbour on the Meuse, allowing stone and supplies to be shipped in from the south

Photo: Scale model (Wikicommons)

Where exactly is “here”?

Maastricht, 150 metres south of the current Sint Servaas Bridge. The Meuse flowed here 2000 years ago about 60 metres closer to the western bank, up to approximately the foot of the Houtmaas. The eastern bank lay roughly in the middle of the present riverbed. Remains of a Roman quay wall have also been recorded there.

The youngest Roman bridge lay between the crossroads Eksterstraat–Houtmaas and the middle of the Meuse today. The earlier bridges lay about 15 metres further to the south.

Photo: Diver Mergor in Mosam 2021 (Harry Lindelauf)

You speak of three bridges. When was the first bridge finished?

The oldest known wooden bridge remains date from the year 38. Around that time the Via Belgica was improved because the military route also became economically important. That was the result of the rise of Roman agriculture in the loess region of South Limburg. The first, probably entirely wooden bridge lay somewhat farther south than the later versions. Under the current part of the Easyhotel on Eksterstraat remains of a bridge pier of the first bridge were found. It is still not clear whether the first bridges were entirely made of wood or already had stone piers. The bridge was probably important enough for the Romans to build a version with stone piers immediately.

And bridges number 2 and 3?

Bridge number two follows around 226 and, like the first bridge, will last more than a century. In the fourth century a new bridge is needed again. The remains show: the Romans now build a 200-metre-long bridge with a stone pier every 12 to 15 metres in the riverbed. The superstructure is executed in wood. The story goes that this bridge collapsed in 1275 during a parade or procession under the weight of the people. That story seems unlikely: the third Roman bridge would then have lasted 900 years.

Such a Roman bridge—does it resemble the current Sint Servaas Bridge?

No. That bridge is entirely made of stone. Or rather: of modern concrete. The bridge was rebuilt in 1932 in concrete, the exterior consists of natural stone cladding.

Photo: Lion statue (Wikicommons)

Back to the Romans. How did they build a bridge in a flowing river?

For a wooden bridge they drove oak piles and beams about 30 centimetres thick into the limestone layer of the riverbed. They used a pile-driving installation on a raft. Iron pile shoes protected the beams and piles during the driving.

For wooden piers two rows of piles were driven parallel between the banks at an interval of about six metres. Crossbeams between the rows made the construction strong enough to place a deck of wooden beams on it. The bridge deck lay several metres above the water to avoid hindering the passage of their river ships.

So a bridge with stone piers was not built like that?

No. To build the piers, a dry work pit was necessary. This was constructed by making two sheet piling walls, close to each other, from beams driven into the riverbed. The sheet piling was made watertight by filling the space between the two walls with fat clay. Then the water was removed from the work pit. For this they used an Archimedes’ screw or a chain of buckets driven by a waterwheel on a raft.

When the work pit was dry, a heavy timber frame was laid on the riverbed. The frame was anchored to the bottom with driven piles. The space of the pier was then filled in Maastricht with pieces of flint and marl. Large hardstone blocks on the outside protected the filling of the pier against the current. These stones came from, among other things, Roman funerary monuments.

This sounds like craftsmen who knew what they were doing?

Absolutely. With the limited tools they had, the Roman craftsmen managed to deliver top-quality work. Engineers, stonemasons, carpenters, architects, surveyors — hats off to their precision, inventiveness, planning and organisational skills, and perseverance. Much of the equipment they used has hardly changed in form over all those centuries.

Photo: Tombstone used for the bridge (Limburgs Museum)

What remains after 2000 years of all that craftsmanship?

Above water obviously nothing at all. Thanks to the divers of Mergor in Mosam we know that on the Meuse riverbed many things still lie: heavy oak piles, beams, stone blocks, pile shoes, pieces of Roman concrete mortar, clamps and fragments of stone funerary monuments. Remarkably, several beam frames lie on top of each other. Most likely the frames are remains of the foundation for the stone piers.

Where have the other parts of the bridge gone?

Until the raising of the Meuse water level by the construction of the Borgharen weir in 1929, a kind of dam of construction remains was still visible at low water. Much of this has disappeared. Main causes: the construction of the Liège–Maastricht canal (around 1850) and the deepening of the navigation channel in 1963. The turbulence from the screws of the river cruise ships that dock today is also damaging the remains. And that while the remains have been an official national monument since 2017.

What can still be found?

Investigations have recovered dozens of finds, including metal objects such as nails, clamps and pile shoes. Remarkable is the discovery of a Roman roof tile with the circular stamped text “VEX EX GER”. The abbreviation stands for “Vexillatio Exercitus Germanici inferioris”, according to former city archaeologist Titus Panhuysen the name of a cohort of 2nd-century engineering troops for the construction and maintenance of bridges.

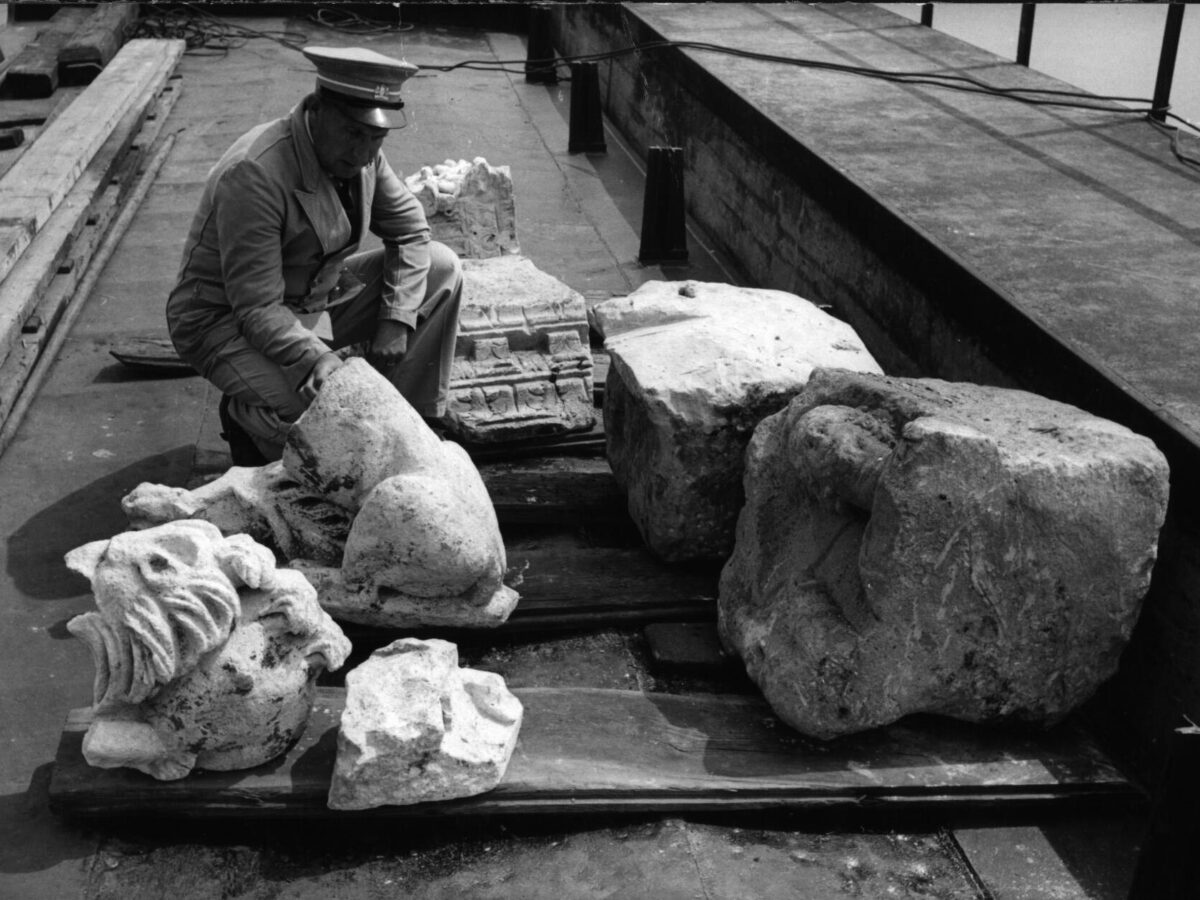

During the 1963 investigation fragments of tombstones and stone statues were recovered. The Romans used the valuable stone material to fill the foundation of the bridge or to protect it against the current. The finds are stored in a municipal depot. Two stone blocks with sculpture and an inscription can be seen in Coffeelovers Annex on Plein 92.

Photo: Dredging finds (HCL/Fotopersbureau Het Zuiden)

What is next for this national monument?

Your question is topical because of the high water in July 2021. The flow rate of the Meuse together with sand, stones and waste carried along causes considerable erosion to the bridge remains. It has also become clear that the stone quay walls and the arches of the Servaas bridge form a dangerous bottleneck at high water. Authorities are now looking at this. But whoever tackles this bottleneck must also find a solution for the Roman bridge remains. The choice will be: protection by covering, or excavating and conserving on land and perhaps partly reconstructing them.

With thanks to Gilbert Soeters, municipal archaeologist Maastricht.