The Happiest Pig in Limburg

Author: Hans Moleman

Photography: Jonathan Vos

They must be the happiest pigs in Limburg, the Bentheimers on the Heerdeberg estate. No, in the whole country. Just imagine: their own free-range garden the size of a large football pitch, spacious shelters – and as a bonus also the most beautiful view of Maastricht. La vita è bella in the pig field on the western flank of the Margraten plateau, high above Heer.

oftly grunting, the old guard – mottled black-beige specimens nearly two metres long – lies in the loose earth, while the youngsters a bit further on shuffle around and make curious sprints to the fence whenever a visitor appears there. The Bentheimers are not just any pigs. They are real primal animals, which somewhat resemble the pigs the Romans brought to these regions almost two thousand years ago. On the Heerdeberg they are cherished, only to end up, after a beautiful life, on the plates of the estate’s guests. Butcher-cum-chef Coenraad, who together with his Sanne runs eatery Bij de Paters there, guarantees juicy Bentheimer meatballs, chops, and sausages.

Useful Omnivores

The pig is a striking example of the changes that the Romans once brought about in the hilly land of Limburg. They were colonial occupiers, almost two thousand years ago, but as often happens with foreign powers: they also brought useful things. Also in terms of food. For example, they introduced cherry trees here, walnut, chestnut and plum trees. As far as livestock was concerned, the influence was even greater: they brought Roman chickens, cows, and pigs.

In this way the Romans ensured that the roughly 200 thousand indigenous people who at that time inhabited the area that is now called the Netherlands – there were not yet any more people living in the swampy delta of Rhine and Meuse – gradually saw their diet change.

When thinking of pigs, the image you still have in your mind’s eye today is of many animals in a long shed with a concrete floor. On the Heerdeberg you see them once again in their element; by origin they are in fact real outdoor animals. As omnivores, pigs clean up the surroundings, from insects and carcasses to acorns, twigs, weeds, and leaves. By nature they are useful: with their strong snouts they turn over the soil so that new plant species get a chance.

In the past, already in Roman times, you would find pigs in almost every household. In every village there was at least one swineherd who, early in the morning, blowing his horn, walked past the houses to pick up the pigs one by one. He then drove the whole crowd to places in nature where food could be found.

Fruity Heritage

For South Limburg, the fruit cultivation that the Romans introduced has proved to be of lasting value. Cherries, walnuts, chestnuts, and plums were previously still unknown in this region. Now these fruits have been part of the regional cuisine for centuries – and especially the cherry still manages today to remain a highly valued summer fruit.

Of the cherry it is known that it was once brought to Southern and Northern Europe by a Roman field commander from a region in Anatolia on the Black Sea – now Turkey. Turkey was and is cherry country par excellence: it is now the largest producer in the world, with an annual harvest of more than half a million tons of the small red fruits.

In South Limburg the traditional cherry trees – the tall standard trees – have slowly but surely disappeared from the landscape over the past century, apart from a few beautiful hobby orchards. It became too expensive to pick the large trees and to protect them against birds. However, cherry growing has bounced back: in the last decades the traditional tall standard fruit has been almost completely replaced by more manageable low-stem trees.

Dark Red Giants

You see these low trees, for example, in the hills just east of Maastricht, near villages such as Bemelen and Cadier en Keer.

At the crossroads just outside Bemelen, on the side road to Cadier, stands a beautiful field of low cherry trees belonging to the Leesens family, who own the Bemelerhof on the other side of the village.

At the family business, a characteristic carré farm dating from 1922, fruit juices and jam are made and sold per bottle and jar in the farm shop.

The Bemelerhof also has a special product: wine brewed from their own cherries, aged in the cellar. Red wine with a special cherry-like finish, which according to the growers suits a summery meal very well.

What are actually the tastiest cherries? Those are the Kordia — large, deep dark red giants with a fine flavour and an excellent bite.

“People always ask for them in summer,” says Mrs Leesens. “Are the Kordias already there?”

But this favourite fruit ripens late in the cherry season, which begins in July. So real lovers must be patient.

“For South Limburg, the fruit cultivation introduced by the Romans has proved to be of lasting value.”— Hans Moleman

Roman Rooster

And the chickens — what about them?

Before the Romans came to South Limburg, no poultry roamed this region. The Romans brought their own specimens. An authentic Roman chicken can be recognised by its legs: they have five toes instead of four. Over the centuries, that extra toe did disappear here.

In Klimmen you can see what ancient poultry looked like. There, at Villa de Proosdij, chickens and roosters of a primal breed from Roman times roam — animals with five toes.

The Roman roosters are especially impressive: large proud animals with raven-black plumage.

Roman South Limburg is particularly tangible at De Proosdij.

The land around the villa was once part of one of the largest Roman estates in Europe, Villa Voerendaal.

Various finds, such as nails, pottery and roof tiles, point to ancient activity here.

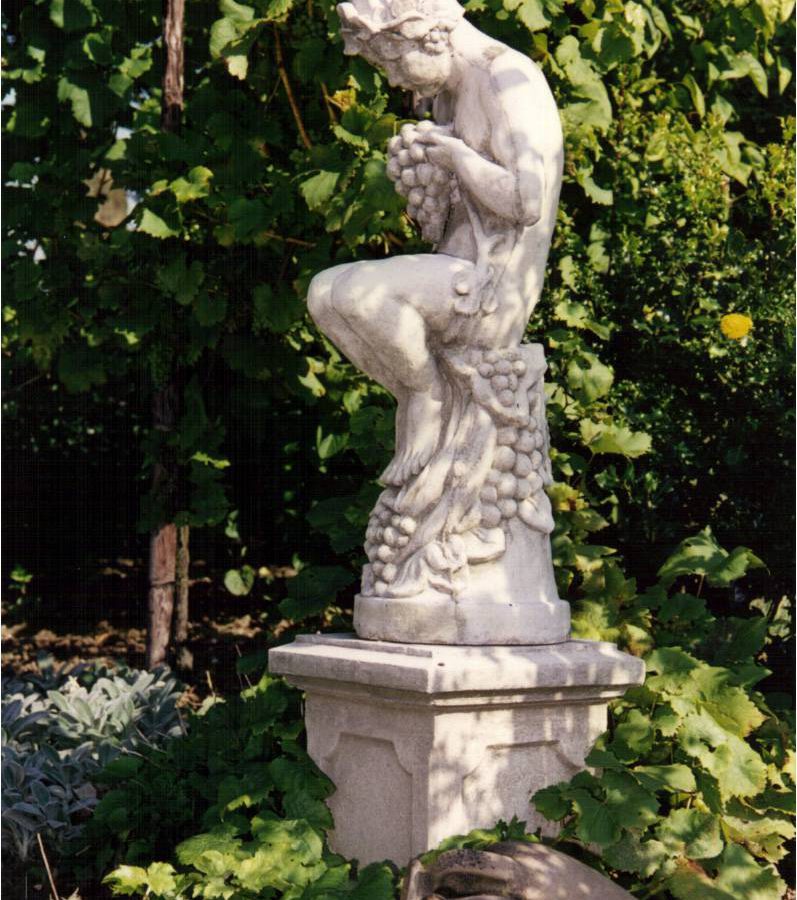

Now the villa on the Klimmenderweg is dedicated to the Roman past. The Habets family has laid out Roman gardens, which can be visited on weekends. After 2,000 years, the garden of Pliny the Elder blooms again, just like the fruit trees the Romans brought to South Limburg. Own bees collect nectar from ancient plants, and the vineyard offers a beautiful view of Heerlen, which in Roman times was a significant fortified town.

Warm Wine

Does wine cultivation in Limburg also date from Roman times?

Probably not.

Because the Romans preferred to bring their own wine ready-made from the warmer regions of their empire. Only in the year 968, hundreds of years after the Romans had left Limburg, was wine cultivation first mentioned in official documents — an inventory list of Queen Gerberga of Saxony — referring to vineyards near Maastricht.

That vineyards have existed in Limburg for over a thousand years is logical: the region is favourable due to its slopes and fertile loess soil.

From Maastricht, viticulture spread along the Geul and Jeker rivers through South Limburg.

In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the hills around the Meuse and Geul valleys were largely covered with vines and Dutch viticulture was at its peak.

After that it gradually declined. Wine faced competition from beer — and after 1540 the climate changed. It became colder in the Netherlands, a so-called Little Ice Age arose, and the Eighty Years’ War came on top of that.

The final blow came from a special combination: the grape louse struck and Napoleon prohibited — to protect the French wine industry — the cultivation of wine in the Low Countries, including Limburg.

Stroberger White

Fifty years ago the time was ripe for a revival.

The Apostelhoeve in Maastricht began planting vineyards, thus restoring a centuries-old tradition in the region.

Today there are fifteen commercial vineyards in South Limburg, and at least as many hobby vineyards.

Such a hobby vineyard can be found in Bemelen, where Domein de Stroberg produces the Stroberger Witte: Limburg country wine from the same village where the cherry wine is made.

The vines grow on a sloping field along the footpath that climbs steeply to the Bemelerberg.

Where can you buy the Stroberger?

Ask around in the village and you will eventually find out.

And otherwise, you leave Bemelen with a bottle of real Limburg cherry wine. Also special.