Is it in our family? Traces of Roman families in Rimburg

Author: Christian Kicken

Photography:

“Who writes, remains,” says a well-known saying. That was already true in Roman times, because countless stones with inscriptions show many names, also from the Roman north. Special are the tombstones found in Rimburg along the Via Belgica: they point to three local families.

Between 1926 and 1929, the Aachen archaeologist Otto Eugen Mayer led excavations on the grounds of Rimburg Castle, right on the border between Rimburg (NL) and Übach-Palenberg (DE). He discovered remains of a Roman roadside village that had developed from the middle of the first century on both sides of the Worm. Characteristic for the village were a bridge and the Via Belgica. The road and the bridge were thoroughly repaired after more than 250 years of use in the first half of the fourth century. Otto Mayer found, among other things, remains of the wooden bridge structure and 14 ancient tombstones. The stones are—except for one—now in the possession of the owners of Rimburg Castle.

Photo: reconstruction of the Roman roadside village near Rimburg. Illustration by Mikko Kriek.

Relatives?

In 2019, archaeologists Hilde Vanneste and Uta Schröder published a major study on Roman Rimburg. As part of that research, the German researcher Janico Albrecht examined the special collection of tombstones, most of which are made of sandstone from the Nivelstein quarry, a few kilometres upstream along the Worm.

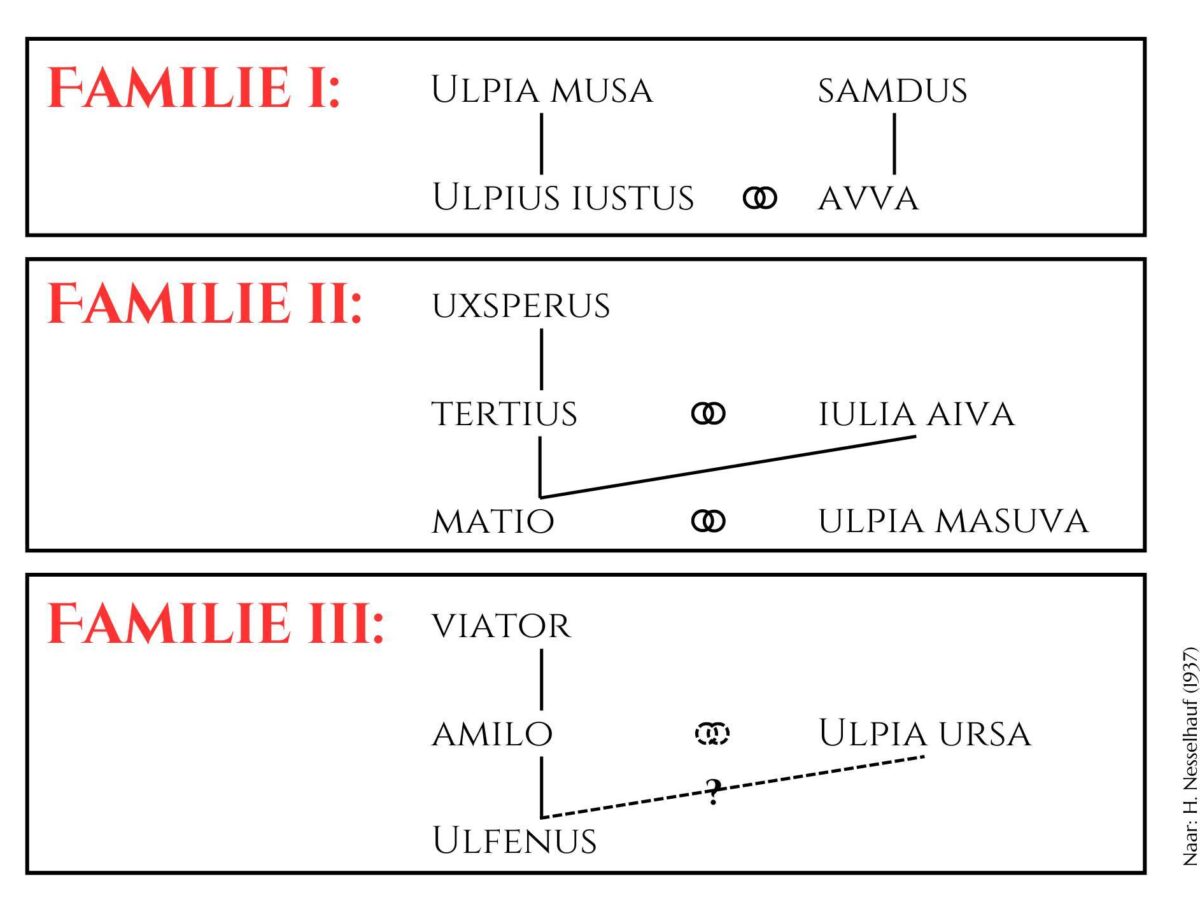

The “Rimburg” tombstones are fairly typical examples for the Roman north. They are elongated, have a Latin inscription with names, and some are decorated with leaf and flower motifs. Nevertheless, another German researcher, Herbert Nesselhauf, already noticed something remarkable in 1937: some names appeared more than once on different stones. Could they perhaps be… relatives? He worked out the family trees of three families that he was able to distinguish.

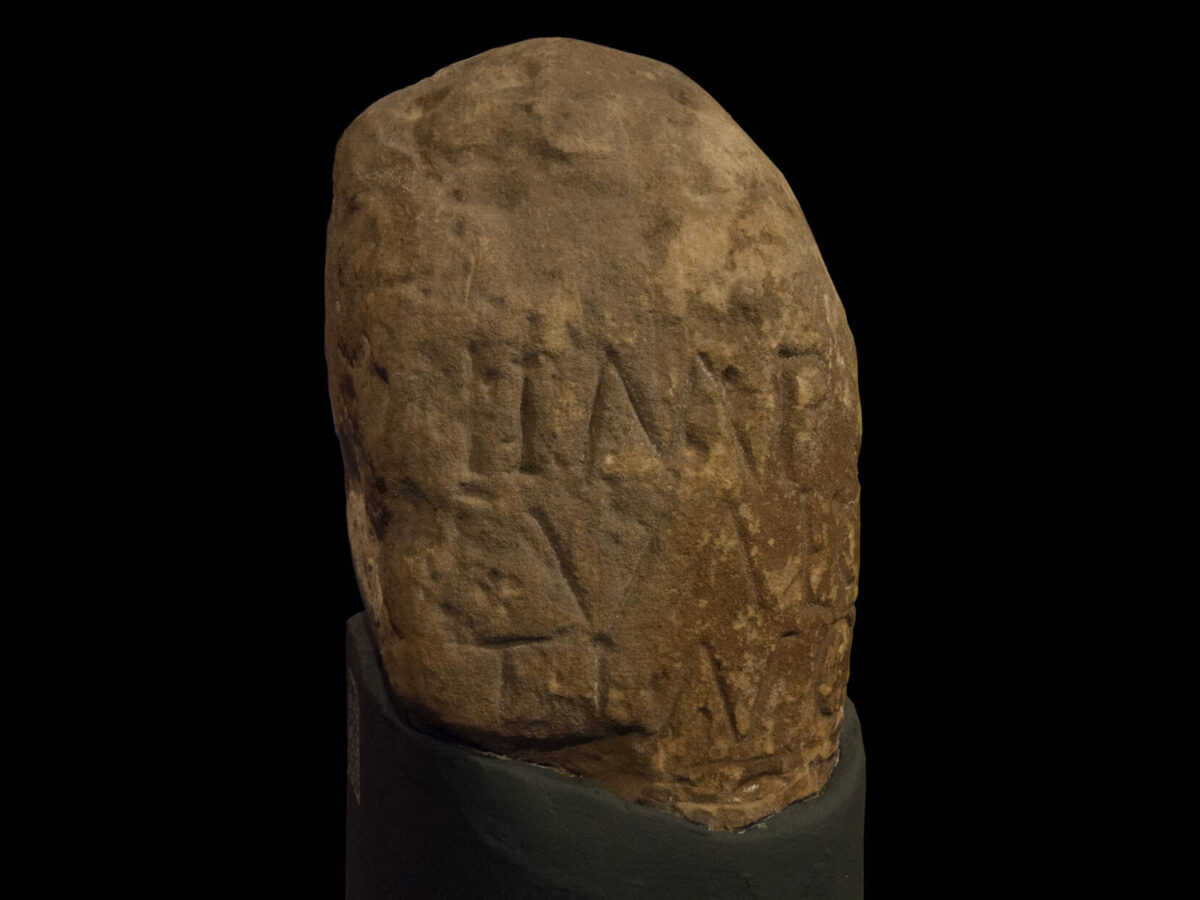

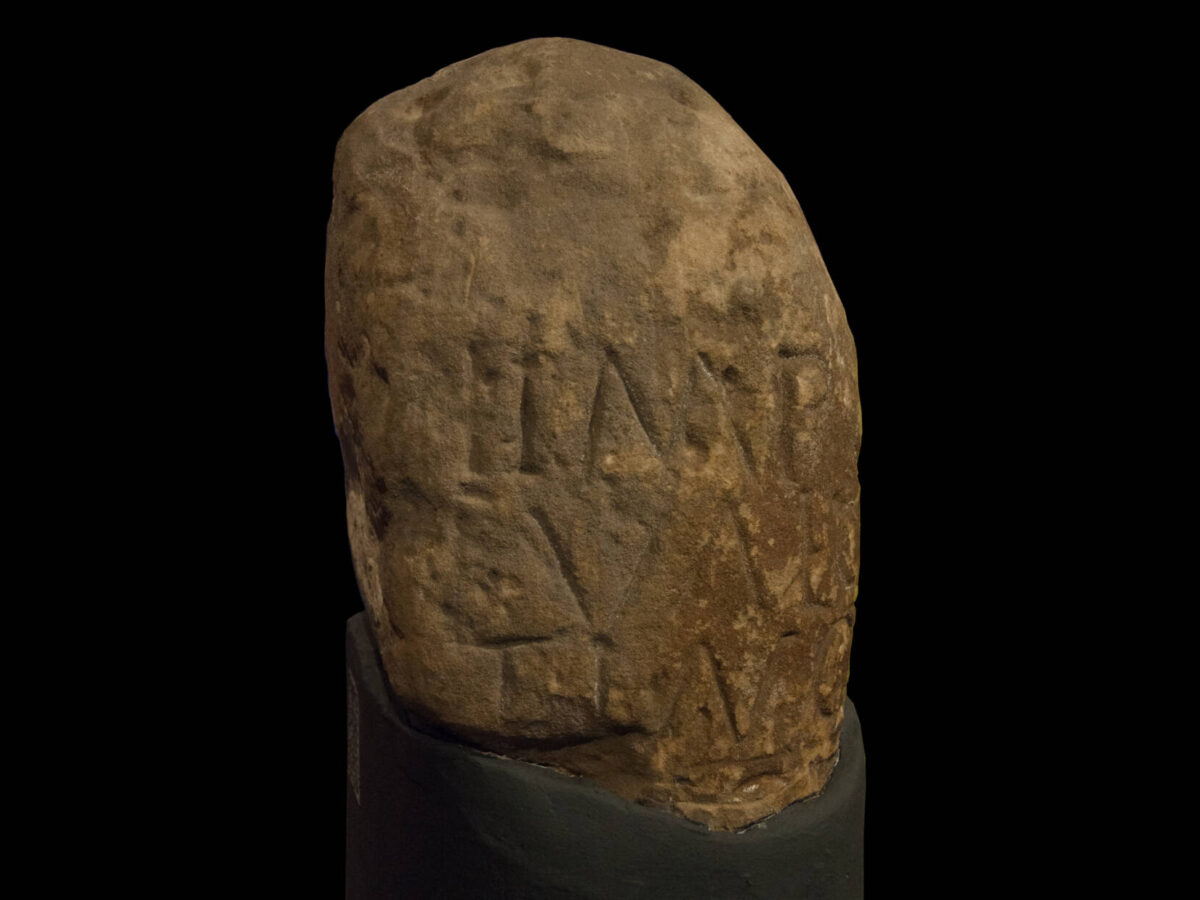

Photo: tombstone of Ulpius Iustus. City Archive Aachen.

A popular emperor

The family members, probably villagers, have names with a Roman, Gallic or Germanic sound. That was quite normal in this part of Roman Germania, which bordered Gaul. One particular name stands out: the male name Ulpius and the female name Ulpia.

Janico Albrecht offers several explanations for this: first, he points to the reign of Emperor Trajan (98–117), whose “surname” was Ulpius. Perhaps villagers, possibly former soldiers, named their child after the emperor as thanks for a favour from the imperial court. A second explanation: the children were named after groups or places referring to the emperor, for example the 30th Legion Ulpia Victrix, or the cities Ulpia Noviomagus (Nijmegen) or Colonia Ulpia Traiana (Xanten).

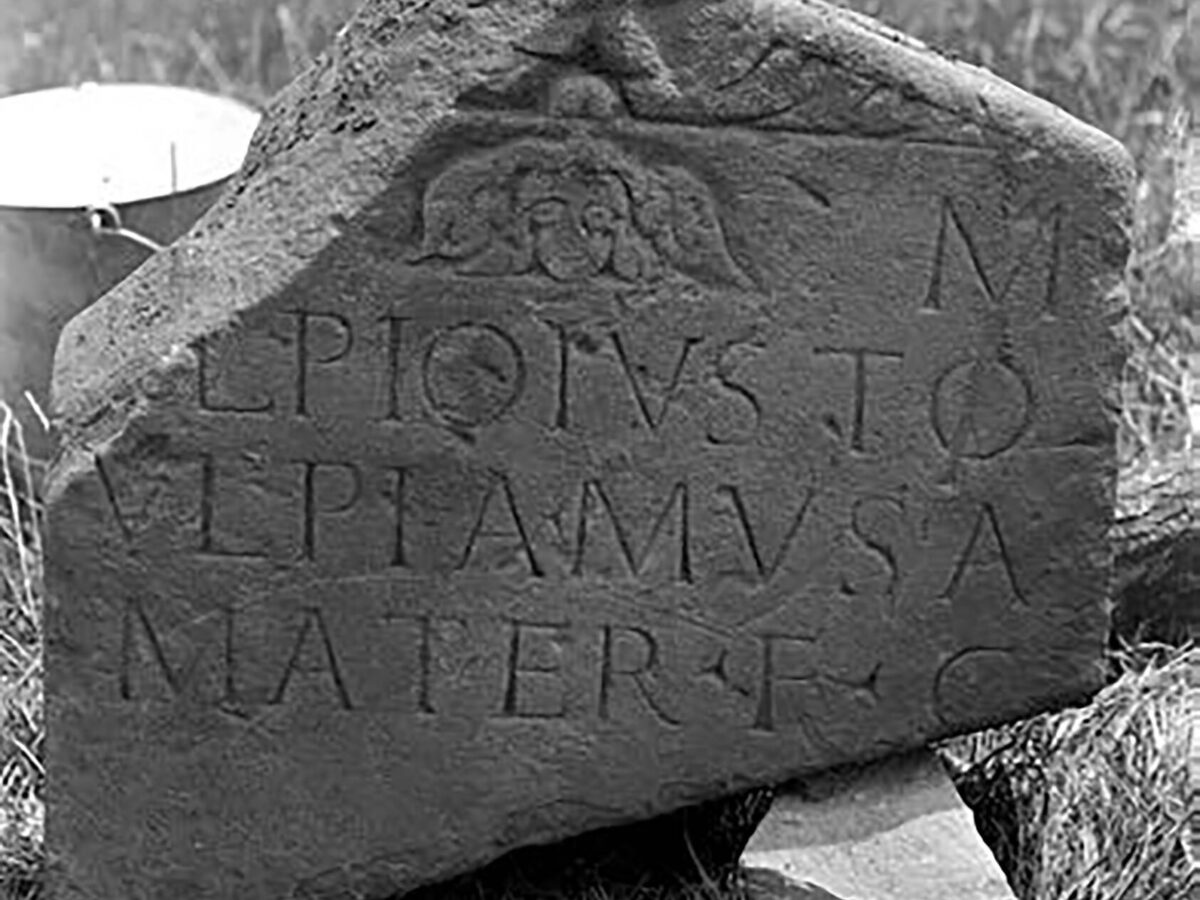

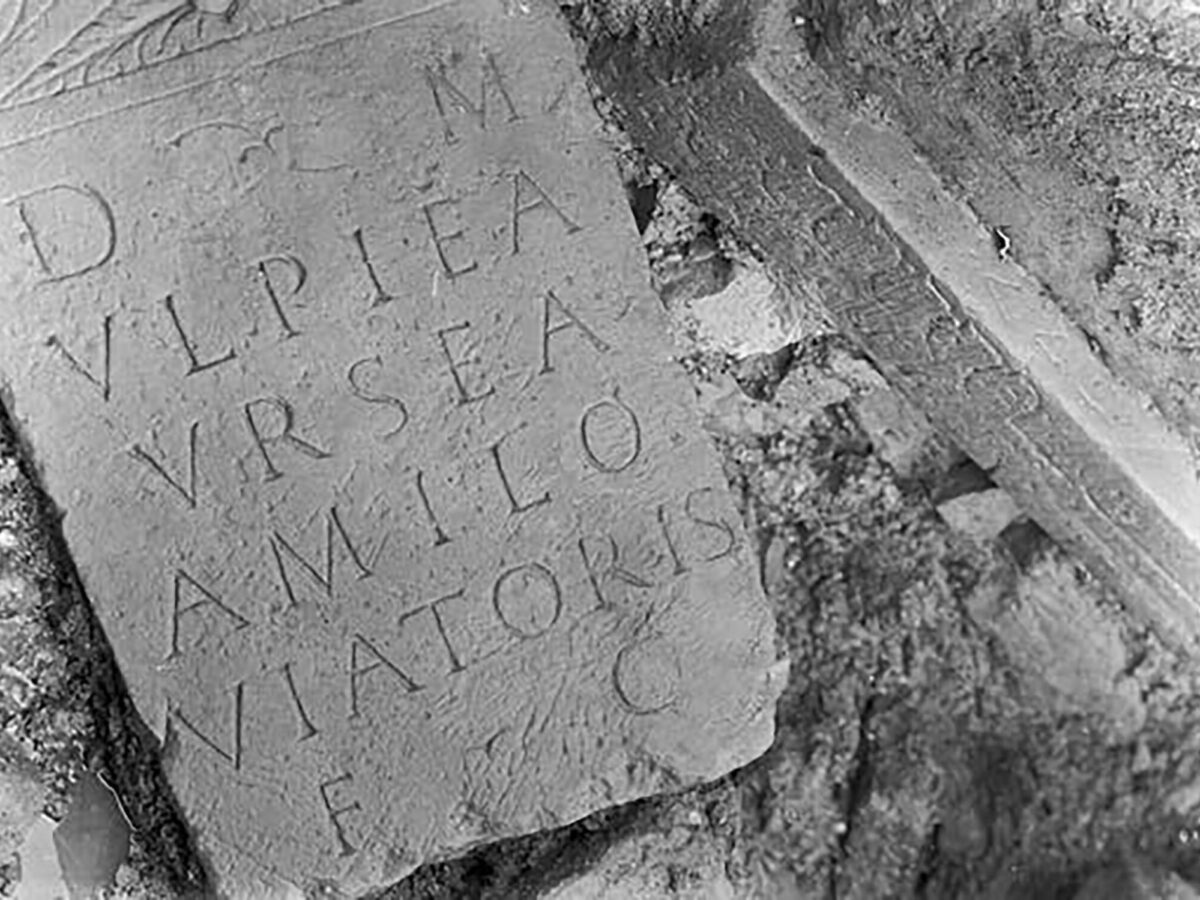

Photo: tombstone of Ulpia Ursa. City Archive Aachen.

Wolf children

Albrecht has a third explanation. One of the tombstones mentions Ulfenus, son of the woman Ulpia Ursa. Now, the Germanic “Ulfenus” and the Latin “Ulpius” both mean “Wolf.” Was “Wolf” or “She-wolf” a popular name in the various languages spoken in the village? If so, then mother Ulpia Ursa was a true animal lover: her name means “She-wolf Bear.”

The find in Rimburg is remarkable, because it almost never happens that Roman tombstones of family members are found together. And without similar finds elsewhere, it remains guesswork to find the right explanation for the Rimburg tombstones.

Photo: three families according to the tombstones, overview after Nesselhauf (1937).

Sustainable fellows, those Romans

The population of Roman Rimburg must have drastically declined at the beginning of the fourth century. During decades of unrest in the Roman Empire, villagers left for a better place to live. Emperor Constantine (312–337) restored peace, among other things by repairing roads and bridges.

For the work on the Via Belgica and the bridgehead at the Worm, building material was needed, although that must have been scarce at the time. So the Romans looked for good building stones from older, disused buildings. At the abandoned village on the Worm, old tombstones—perhaps already one and a half centuries old—came in handy. The stones were reused for the bridge, and the rest is history—family history, to be precise!

Photo: excavation of a Roman building near Rimburg Castle. Probably archaeologist Otto Eugen Mayer is visible. City Archive Aachen.

Photo: milestone for Emperor Constantine, found in Eygelshoven. Photo R. Voorburg.