The first city wall of Maastricht was Roman

Author: Harry Lindelauf

Photography: Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Rijksdienst Cultureel Erfgoed, gemeente Maastricht

In 333, the Romans began building a wall to protect their bridge across the Meuse. The first city wall of Maastricht was estimated to be four metres high, 530 metres long, and equipped with ten towers and two gates.

Everyone talks about a Roman castellum, and here you are with a city wall?

Yes, I dare to say so. The Romans built a wall around an area of roughly 14,500 square metres. To me, that looks more like a city wall than a fort, don’t you think? The wall did not protect a single building but an entire complex — including the bridge, a large granary, a building with two semicircular extensions north of the baths, and several other structures. Not the entire interior area was built up.

And by the way: the bridge was also protected on the Wyck side. No remains of that fortification have been found — they disappeared into the Meuse — but they must have existed. It would make no sense to defend a bridge on only one bank.

What did that city wall look like?

Thanks to research by archaeologists Eric Wetzels and Gilbert Soeters, we have a fairly clear picture. The wall was built of coal sandstone, brought in as small stones from the Ardennes. Marl from the Meuse valley was also used in the mortar—the same materials, incidentally, as those used in the city wall built around 1229. The Roman construction consisted of two walls placed close together; the space between them was filled with mortar and stones. Every 50 metres stood a round tower, and the two entrances, each 3.40 metres wide, were flanked by rectangular towers. In front of the wall, the Romans dug a ditch nine metres wide and four metres deep.

Why was a city wall built?

Constantine the Great completed a new defensive strategy for our region. Previously, the Rhine itself was a well-guarded frontier. But raids by Germanic tribes showed that the hinterland was poorly defended when the frontier troops failed. The Romans switched to a zone-based defence. Stone fortifications were built in Cuijk, Nijmegen, Aachen, Tongeren, and Maastricht. Heerlen also had a fortification — proven by ditches found near the Thermenmuseum and the Tempsplein. Along the main roads, a network of watchtowers was erected to monitor and warn. The foundations on the Goudsberg near Valkenburg-Walem, in use in the same period, were probably from such a watchtower. Smaller military units intervened from the fortifications when danger arose.

That construction must have been a colossal job

Indeed. We are talking about more than 4,000 square metres of wall, ten towers five metres high with a diameter of nine metres, and two towers beside the gates. It has been calculated that digging the ditches required the removal of 6,500 cubic metres of soil. The building stone came largely by flat-bottomed boats along the Meuse from the Ardennes — a massive logistical operation requiring careful planning.

And who was the lucky contractor?

Only one party fits the bill: the army’s auxiliary troops. They had the knowledge and the muscle to carry out this project. But whether they were lucky — who knows?

What happened to the Roman city wall?

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the Franks arrived. Perhaps church leaders like Lambertus and Servatius resided there, but this has not been proven. Some reports claim that the Vikings destroyed the wall (or fort, or castellum) during a raid in 881. Remarkably, only two larger stone blocks in the right-hand tower of the Basilica of Our Lady originate from the Roman city wall. Everything above ground has disappeared, and no one knows where the tens of thousands of stones ended up.

You say “above ground”—what about below?

That is a different story. Over the years, excavations have revealed foundations beneath the church, beneath the roadway of the Houtmaas, and underneath café Bonne Femme at the Graanmarkt. If you want to explore: on the Houtmaas car park, round metal plates mark the outline of a tower. And in the cellar of Hotel Derlon, you can still see a section of the wall with part of the western gate.

Photo captions

[1] Foundation of the tower at the Houtmaas.

[2] Remnant of the city wall in the museum cellar of Hotel Derlon.

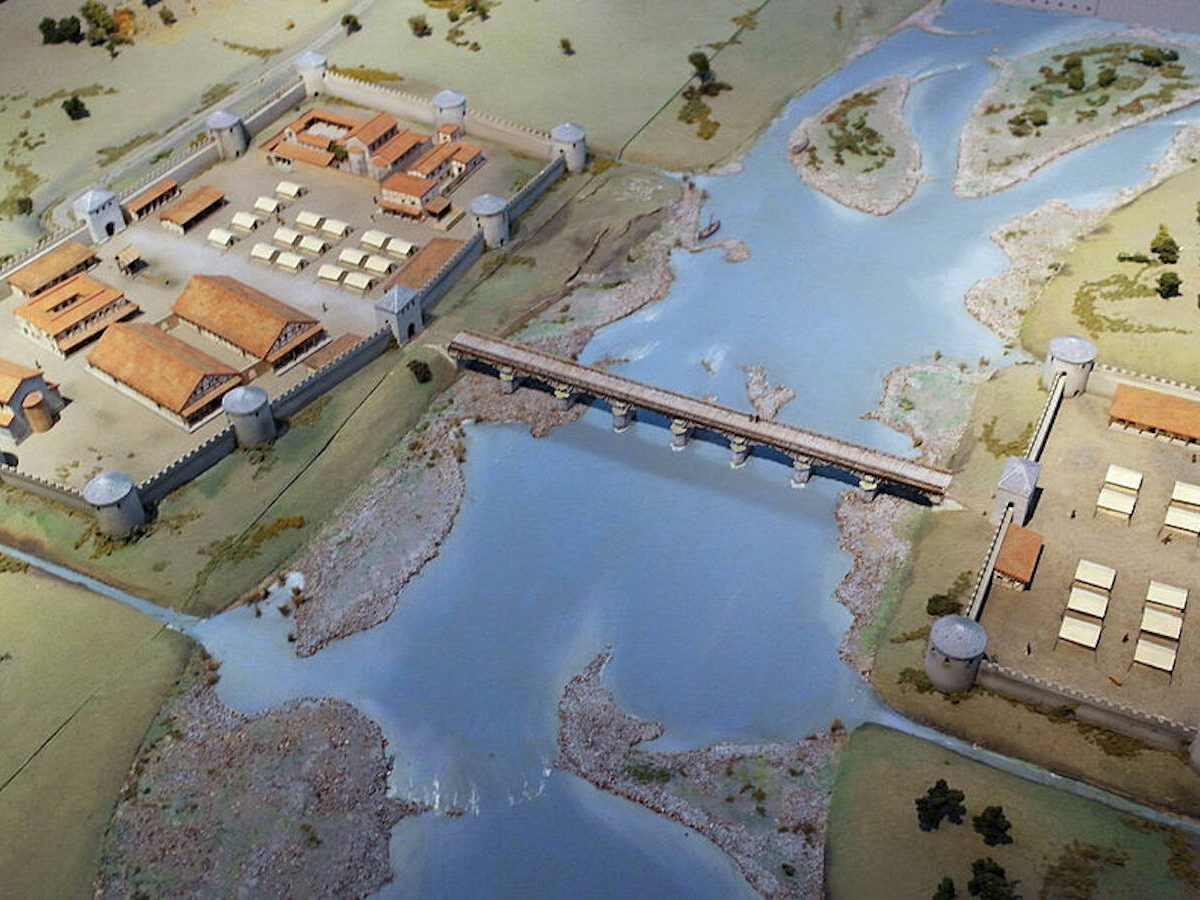

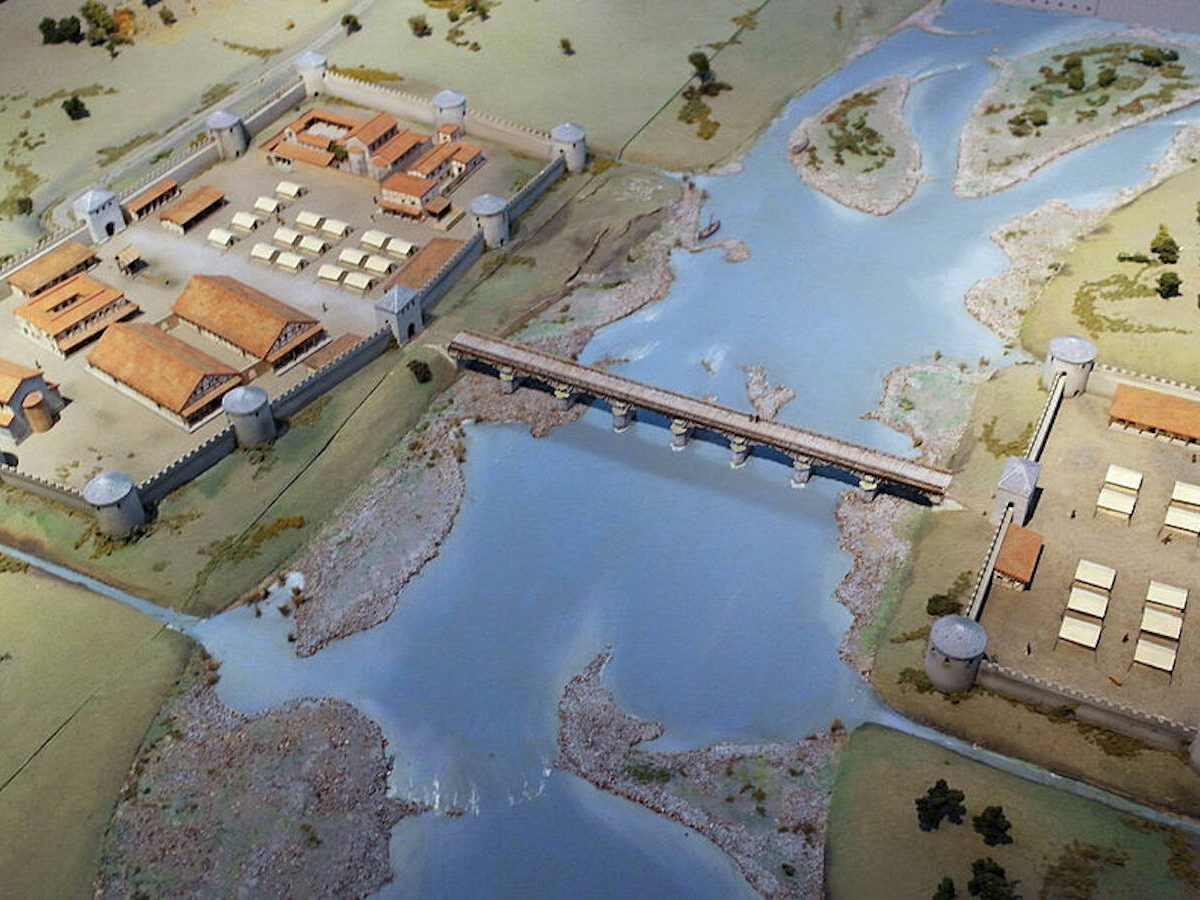

[3] Model of the Roman fortification of Maastricht.

[4] Remains of the Roman fortification incorporated into the Basilica of Our Lady.

[5] Model of the Roman fortifications with an extension on the Wyck bank.

[6] Impression of a Roman watchtower, similar to the one on the Goudsberg.

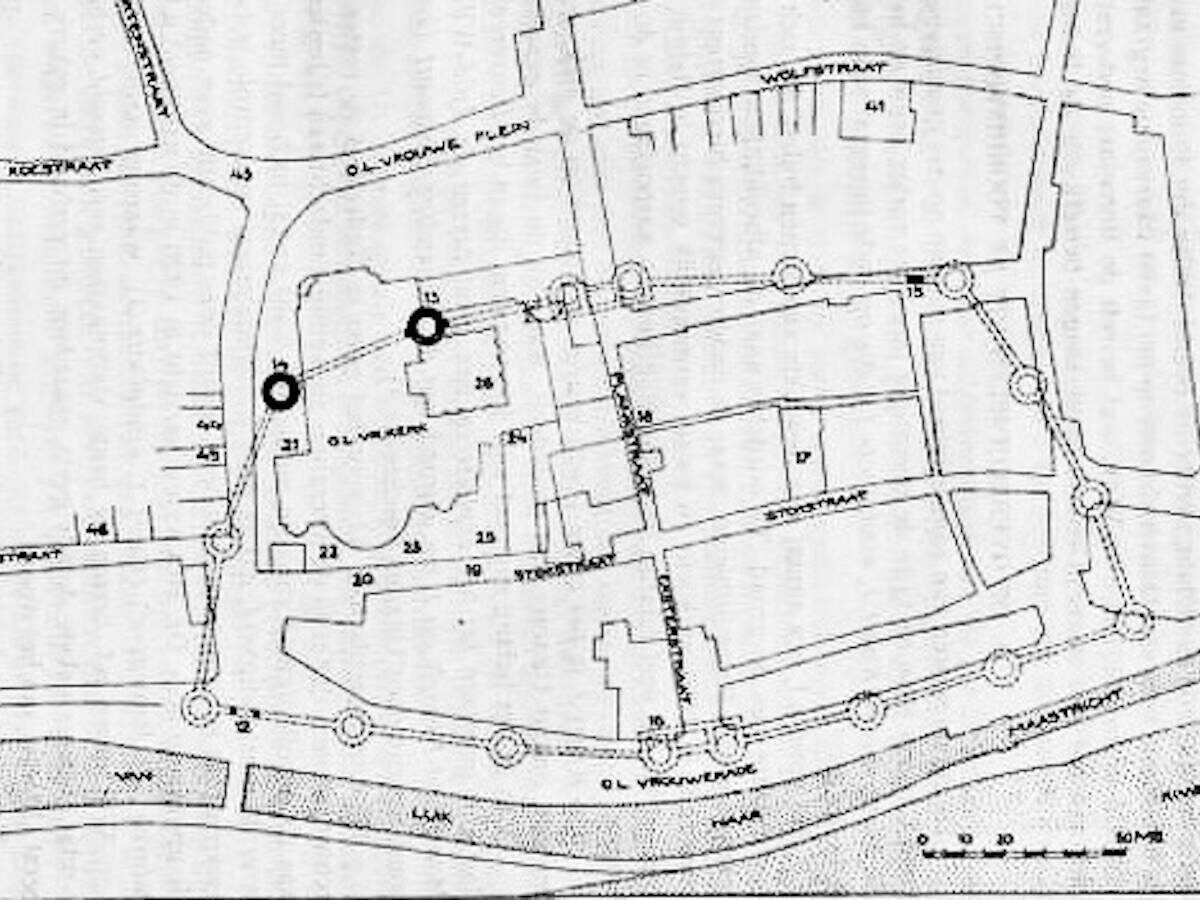

[7] Ground plan of the fortification overlaid on the modern street layout.