Meet these Roman neighbours of the Via Belgica

Author: Harry Lindelauf

Photography: Thermenmuseum Heerlen, British Museum, Wikicommons

We know a lot about the buildings along the South Limburg section of the Via Belgica. But who lived there, and do we know their names? Meet the Romans.

So, did you find a Roman phone book?

Haha, they didn’t know that, and neither do we anymore. I searched for materials that have survived 2000 years and in which names are engraved. I found tombstones, stones with dedications or requests to the gods, pottery and metal plaques. This information comes from publications and reports by researchers and from photos of Roman finds in museums.

Tell us, what did your search reveal?

There are certainly more, but I have identified eighteen names. Of fourteen people, I also know their profession; of the remaining four I know only the name or part of the name. The eighteen were Romans or indigenous inhabitants who lived in the region between Rimburg and Maastricht under Roman rule. Using modern place names, they were residents of Heerlen, Voerendaal, Valkenburg and Maastricht.

Introduce them to us, these Romans? Maybe useful to do that by place.

Good idea. I will start in the east. Heerlen, or Coriovallum, is known for the remains of the baths, but also for its many Roman pottery kilns. When the road to Sittard was constructed in 1837, a Roman burial mound was found. Inside was a bowl of red pottery, signed by the potter Gaius. His colleague Buccus did the same on an earthenware bowl.

But Lucius, isn’t he our local pottery hero?

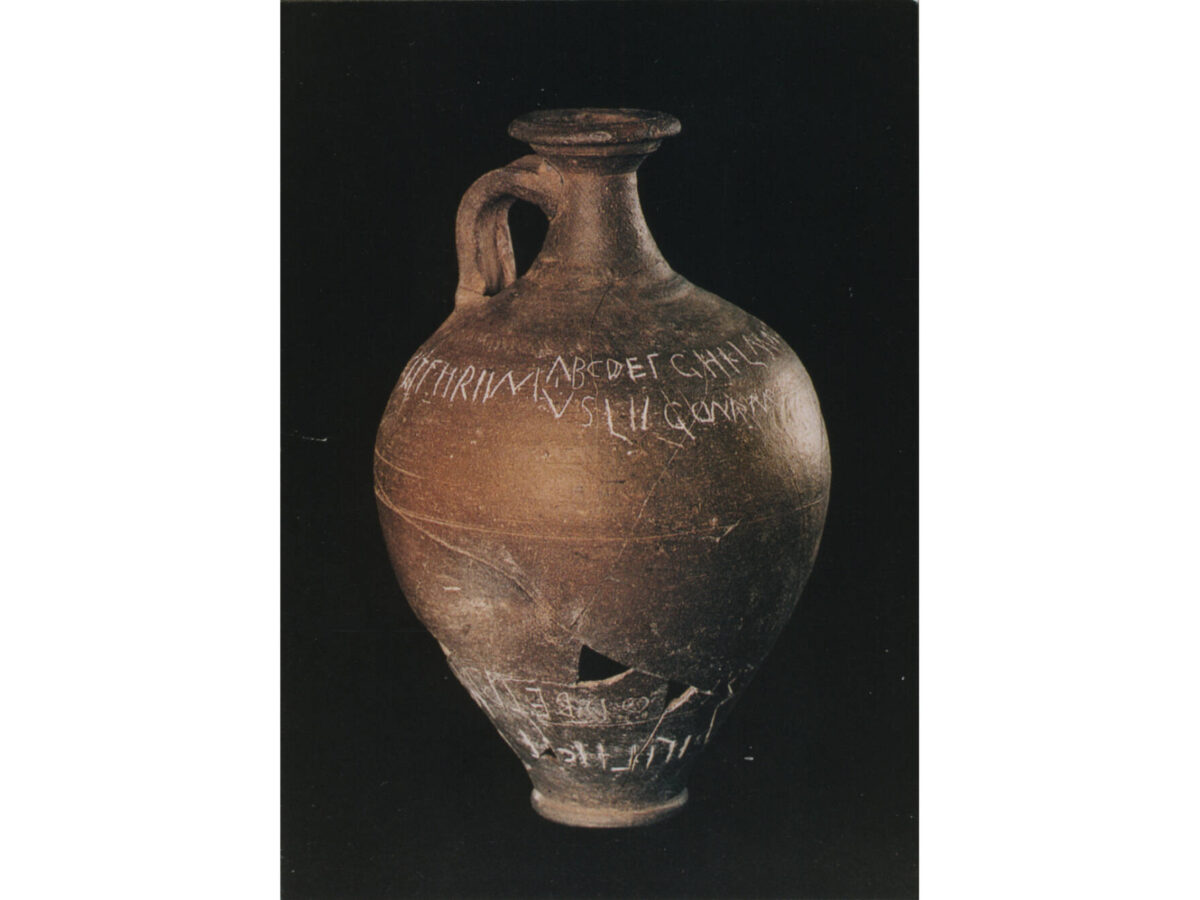

Indeed. Fully named Lucius Ferenius. His second name probably refers to Feresne (Dilsen, Belgium). That makes him an indigenous resident. In 1971, Roman pottery kilns were discovered during excavations at the Putgraaf, on the terrain where the Luciushof now stands. One of the kilns exploded — thanks to a firing mistake. In the kiln lay sherds into which Lucius scratched three sentences: ‘Lucius made this jug for Amaka’, ‘Lucius dedicates this jug to the good god of Ferenio, his homeland’, ‘Lucius, called Metcius, made this jug in his workshop’. So writing went well, pottery a little less. The jug for Amaka may have been intended for his wife. Another possibility: there is a goddess Amaka known from the Germanic or Celtic world, invoked for fertility and a prosperous production.

Do we also know someone connected with the baths?

Yes, that was my next point. The next gentleman is certainly not a potter but a member of the town council of Xanten, the city under which Coriovallum was administratively placed. That council consisted mainly of landowners. I am speaking of Marcus Sattonius Jucundus. He had the Heerlense baths restored around the year 260, an act he had promised to the goddess Fortuna. We know this thanks to an inscribed stone found in 1957 on the baths site. Possibly he fulfilled his promise to Fortuna to earn a safe return from his military campaigns with the Roman army.

I sense a bridge to the next well-known Heerlen resident…

You sense that correctly. We end up in the army with Marcus Julius. He was a soldier in the Fifth Legion, stationed in a fortress near Xanten. He survived his service and went (back?) to live in Heerlen. He probably lived from a piece of land he received as a pension. Which explains why, centuries later, the Dutch pension fund ABP moved from The Hague to Heerlen. The information about Marcus comes from a tombstone of Kunrader stone found in 1873 at the Bekkerweg. I also have a doctor for you — I will tell more when we reach Valkenburg, where we meet his colleague.

Enough of Heerlen. Moving westward, do you know a Roman from Voerendaal?

We cannot skip the enormous Roman farmstead Ten Hove hidden under loess along the Steenweg. Fortunately, sherds of terra nigra pottery were found at this site with the names of a certain Secundio, a Severus or Severianus, and a Roman named Jucundus or Julianus. The uncertainties arise because the letters are hard to read or the names are incomplete. I assume these men worked and lived at the villa rustica Ten Hove.

Not many for such a large farm. Shall we continue?

Gladly. On to Valkenburg-Houthem. There lies a farm in the Rondenbos where bronze plaques with names were found. On one plaque, a certain Julius confirms his friendship with Marcus Vitalinius, a high official and one of the “mayors” of Roman Xanten. On the reverse side of the plaque is a later inscription, showing the tribe of Catualium honouring Titus Tertinius, former official of — again — Xanten. The name Titus Tertinius appears also on the second plaque, a tribute to what is called here a “council member” and “mayor” of Xanten.

Anything more from Valkenburg?

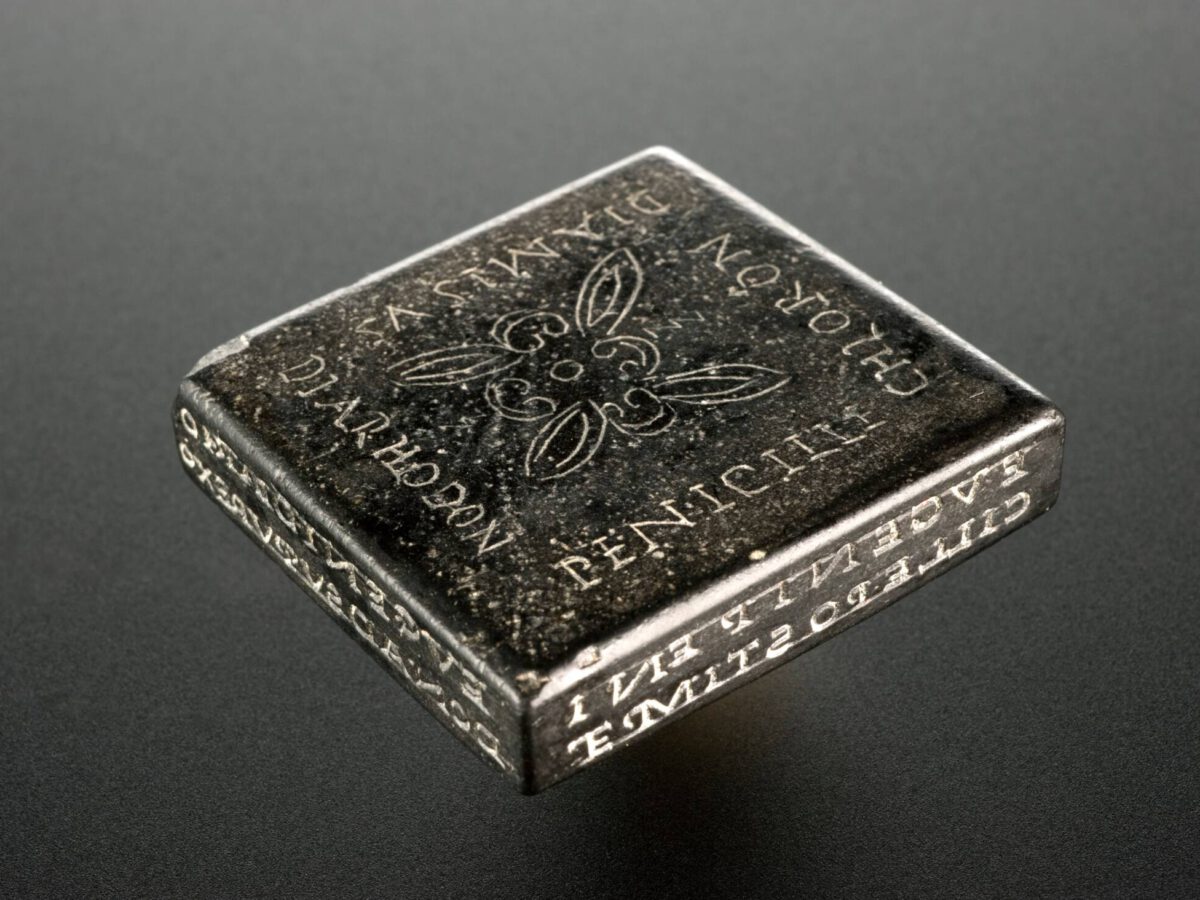

Yes, another gentleman with three names: Cajus Luccius Alexander. We know his name and his profession — domestic and eye doctor — thanks to a stone stamp found in the Ravensbos. The stone bears inscriptions on four sides with his name and the names of eye ointments. This stone is very similar to a Roman find in Heerlen. In 1860, at Villa Beukenhof on the Valkenburgerweg, a stamp was found with the name Lucius Junius Macrinus and ointment recipes.

After Valkenburg, Meerssen and Maastricht come into view.

Meerssen has its beautiful villa Herkenbosch, but unfortunately I could not connect a name to it. In Maastricht I succeeded. Time for some female contribution, in my opinion. Although the name Ammaca or Amaka already sounds familiar. After Heerlen, the name now appears in Maastricht. In 1900 a cellar was dug in the Plankstraat for brewery Marres. The excavation revealed the fragments of a tombstone. The text reads: ‘For Ammaca or Gamaleda, daughter of Verecundus’. Again, a reference to gods instead of a person is possible: Ammaca is originally Germanic or Celtic, Gamaleda is probably Germanic.

That find is in the heart of Roman Maastricht. There must be more there, right?

Nice that you set the bar so high. Can I please you with three more names? On the southern corner of the Plankstraat and the Stokstraat lies a large grain storage facility. In the remains of that building, the square tombstone of Caius Priscinius Probus, son of Pricus, was reused in the foundation.

The same fate befell a part of a funerary tower that one Florius had built for his father. That part was dredged up from the Meuse at the location of the Roman bridge. Remarkably, the inscription on the stone states that the funerary tower cost 14,000 sesterces. Special is the image: a relief of a Roman soldier with helmet and shield fighting a man with an axe.

And last but not least from Maastricht — and even from the Plankstraat: a stone from the cellar of Hotel Derlon. The inscription states that Publius Attius Servatus places a stone, with an engraved request, at an altar for the Parcae, the so-called fate goddesses who decide a person’s destiny. Publius was apparently not very confident about his future when he made his request in the second half of the first century. Remarkably, several centuries later the name Servatus would gain a special meaning for Maastricht.