Hardly anyone knows this remarkable building along the Via Belgica

Author: Harry Lindelauf

Photography: Mikko Kriek

A bathhouse, barracks, dwelling house, farm, pottery or luxury villa — these are the buildings you expect along the South Limburg section of the Via Belgica. One building, however, is hardly known and at the same time very special.

Where are we?

We are standing on the bridge over the River Worm in Rimburg, literally on the border between the Netherlands and Germany.

Why there?

In Roman times there were three villages along the Via Belgica: Maastricht, Heerlen and Rimburg. Maastricht originated because of its bridge over the Meuse, Heerlen owes its existence to the crossroads of the Via Belgica and the Via Traiana (Trier–Aachen–Xanten). And Rimburg had its bridge across the Worm. And in Rimburg lies our remarkable building.

Don’t keep us in suspense — what kind of building was it?

A moment of patience. Because Rimburg was already of importance in those days. On the Dutch riverbank, between the Palenbergerweg and the Worm and along the Via Belgica, the remains of sixteen buildings have been found. These were constructions with stone foundations and timber-framed walls from a certain height. Not small either: an average measurement of 10 by 7 metres. The largest building measured 17.50 by 10 metres with walls 60 centimetres thick. On the German side of the river, buildings of the same type have been found, plus a bathhouse and a pottery with five kilns. There may also be a temple near the Steenenbergweg, where a stone with depictions was found — probably of the gods Minerva (wisdom) and Mercury (trade, travellers). Please note: this is what is known from excavations at a limited number of places so far — there could be more.

The largest building measured 17.50 by 10 metres with walls 60 centimetres thick.—

And all that because of the bridge?

Yes, that is what it comes down to. Many people passed by and therefore money could be earned by caring for people and animals. The potters used the clay of the Worm valley for large-scale production. By the way, the bridge also had to be defended against invading enemies. The German archaeologist Schmidt reported in the mid-19th century that the remains of a Roman fortification lie underneath today’s Rimburg castle, but this has not been proven.

Aren’t you forgetting something?

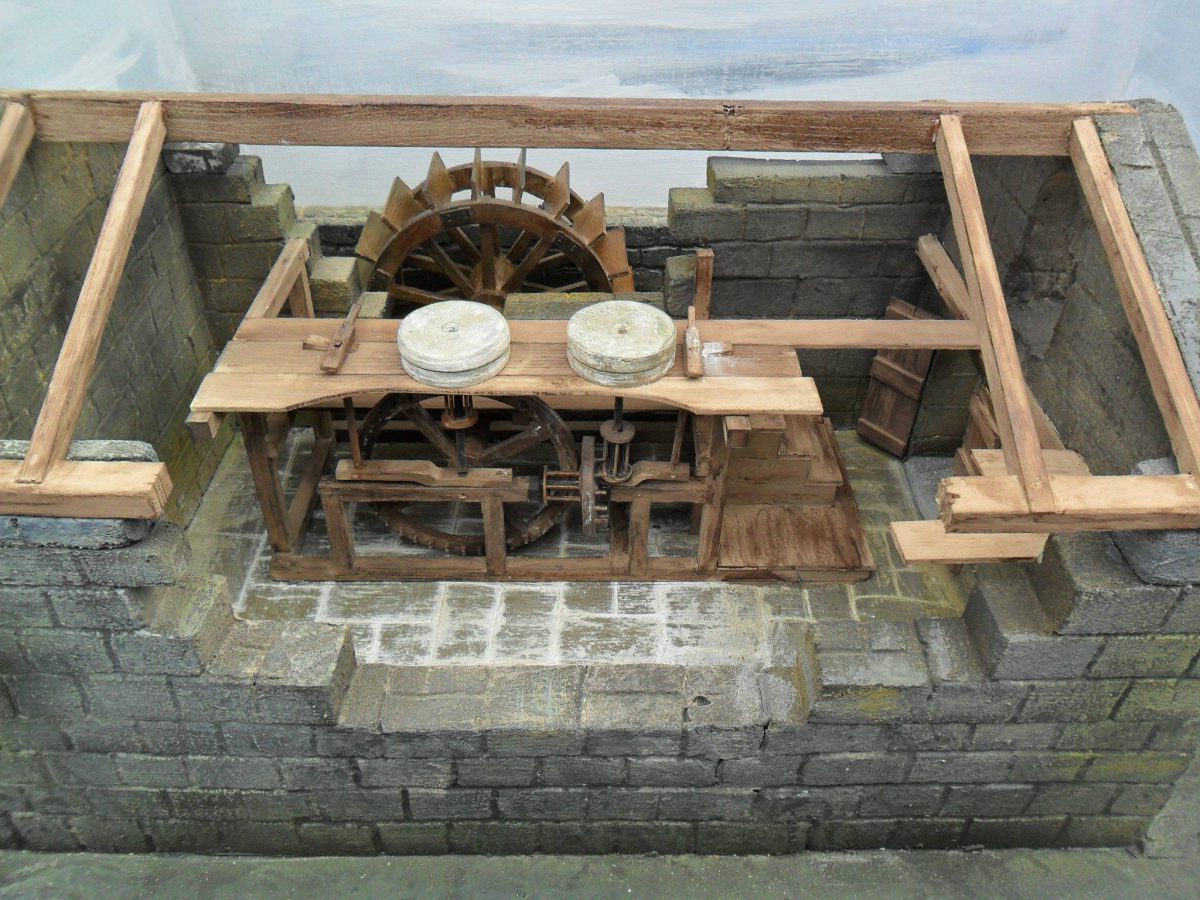

Sorry — yes, the remarkable building: it was a water mill used for grinding grain. The mill was situated right next to the bridge across the Worm. With posts and planks, supply channels were constructed to lead the water from the river to the mill wheel. By narrowing the channel near the wheel, the water flowed faster. The water flow could also be regulated by placing planks. It appears that the wooden structures also formed a kind of quay where boats could be loaded or unloaded

The mill was located next to the bridge over the Worm.—

How do we know all this?

Thanks to excavations by the Aachen archivist Otto Mayer between 1926 and 1929. Mayer found the wooden structures and in one supply channel he found part of a mill wheel with wooden paddles. He also discovered the remains of the bridge and saw how robust it had been constructed. The bridge rested on 30-centimetre-thick oak piles. Some were placed vertically, others diagonally for lateral stability. The bridge was 6 metres wide and had stood for a long period. From time to time it was repaired: new piles were added and old gravestones were dumped around the foundations as protection.

Why is the mill so special?

Along the Via Belgica in the Netherlands, no other Roman mill has been found — in fact, not anywhere else in the Netherlands. The same applies to the discovery of the remains of a mill and a bridge right next to each other. The grain mill was also a fine example of engineering. The vertical rotation of the mill wheel was transferred to a horizontally rotating millstone by two wooden cogwheels. The cogwheels were built in such a way that the millstone rotated five times faster than the mill wheel. The millstones were made in the Eifel out of volcanic stone, but unfortunately they were not recovered. For the record: the Romans obtained the technical knowledge for constructing such a water mill from the Middle East.

Along the Via Belgica in the Netherlands no other Roman mill has been found.—

How long did the mill exist?

The Roman period in Rimburg lasted from shortly before the beginning of the Common Era until about 400 AD — although not exactly known. We do know that all these buildings were constructed in different time periods. Archaeologists distinguish seven building phases within those four centuries. The mill appears to have fallen into disuse around 330 AD. The wooden channels were filled up with earth and stones. Its end may have been caused by the Worm changing its riverbed.

With thanks to Sjef Born.

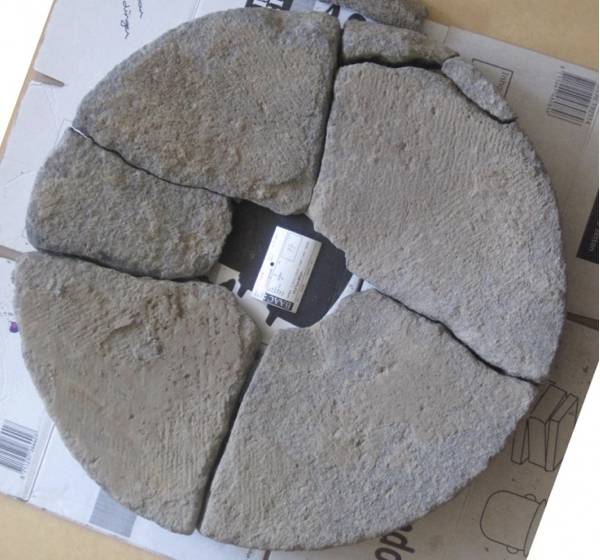

In Hasselt-Ekkelgaarden (Belgium), this Roman millstone was found in a stable. The diameter is 71 cm, the thickness of the rim 9.5 cm. The fragments together weigh about 38 kilos.

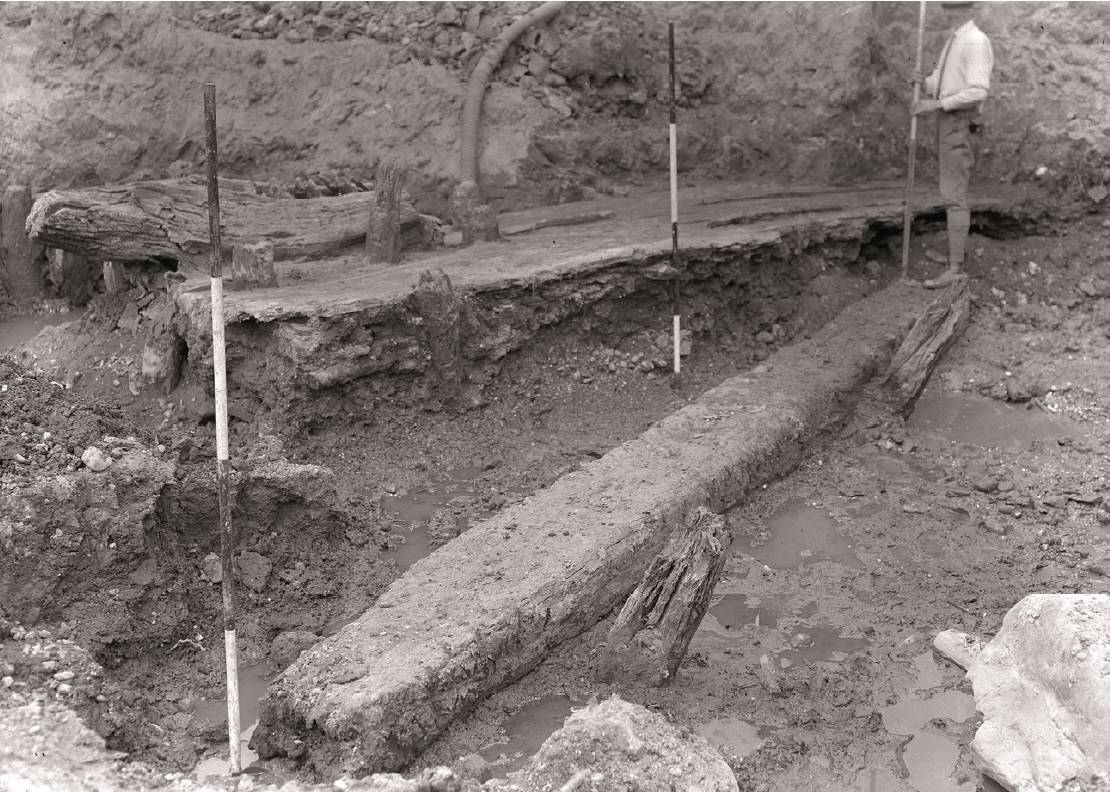

The remains of the wooden mill wheel and the revetment of the channel were found between 1926 and 1929 by Otto Mayer. Source: Stadtarchiv Aachen

The channels provided the supply of water from the Worm to the mill wheel. There may also have been a mill pond to guarantee a constant water supply. Source: Stadtarchiv Aachen

On the right and left sides of the wall, the profile of the Via Belgica is visible.

The construction of the bridge was robust. The foundation piles driven in at an angle provided additional lateral stability. Source: Stadtarchiv Aachen

Model of a Roman watermill.

Source: WikiCommons.

Otto Mayer uncovered the foundations of several Roman houses.