The Story of the Dead Man at the Roman Villa in Meerssen

Author: James Dodd (eindredactie Harry Lindelauf)

Photography: James Dodd

In 1865, archaeologist Jozef Habets discovered a skeleton in the ruins of the Roman villa rustica at Onderste Herkenberg in Meerssen. Unfortunately, the find was forgotten in a museum depot — until it was rediscovered in 2024 and re-examined by scientists. Their research provided some answers, though many questions remain.

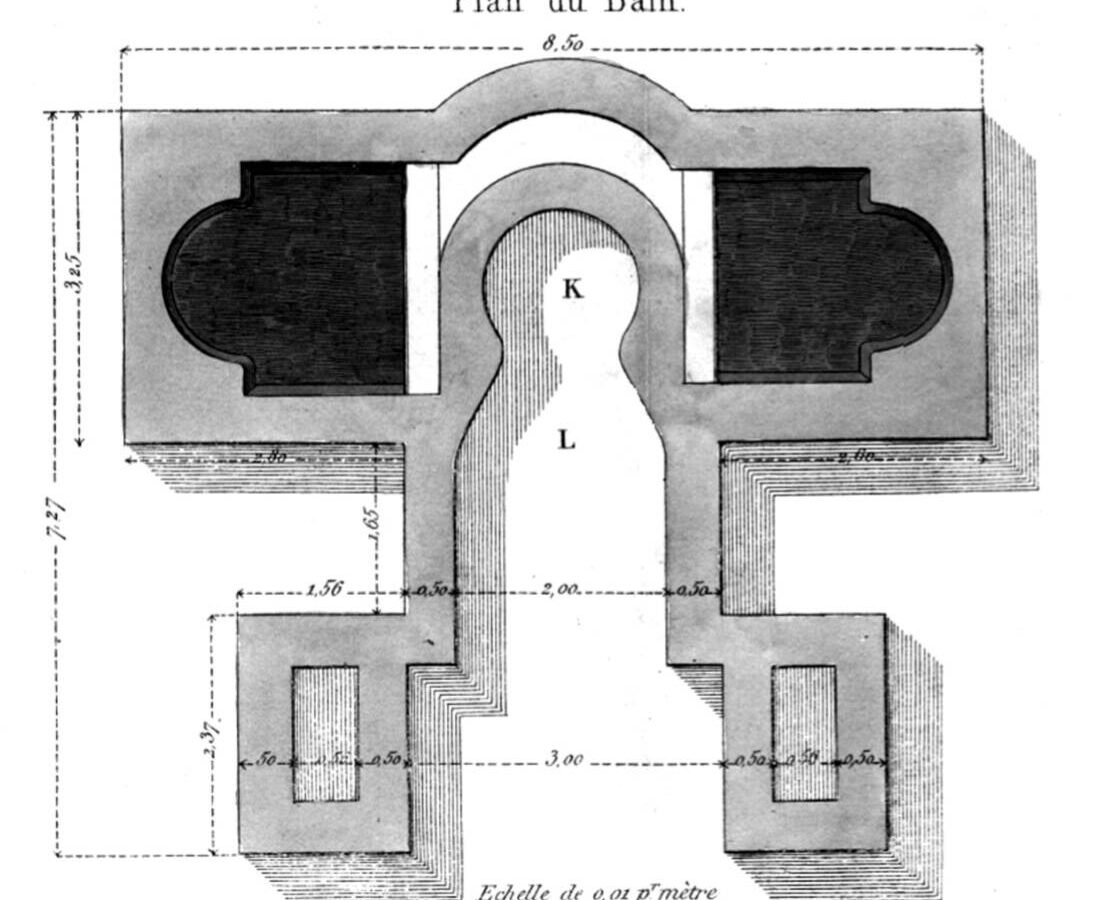

In 1864, Roman remains — stones and roof tiles — were brought to light while ploughing the fields of the Onderste Herkenberg. A year later, parish priest and state archivist Jozef Habets came to Meerssen and began excavations. He uncovered a complex tangle of walls, floors, and rooms. In front of the main building, he saw two adjacent basins, which he interpreted as a bathhouse.

During modern investigations in 2003 and 2014, archaeologists used advanced techniques such as ground-penetrating radar and electromagnetic measurements. What Habets had assumed to be a bathhouse turned out to be two water basins, probably ornamental ponds. These new studies also revealed that the villa complex once included a separate and quite large bathhouse.

A Gift to Liège

Between the two basins, Habets found a skeleton. It lay face down, with the right hand on the back of the head. The body had apparently been buried without covering, grave goods, or any accompanying material. In 1866, Habets sent the skeleton to a museum in Liège as a gift to the Belgian state, since at the time, Liège was regarded as the academic center for the Limburg region.

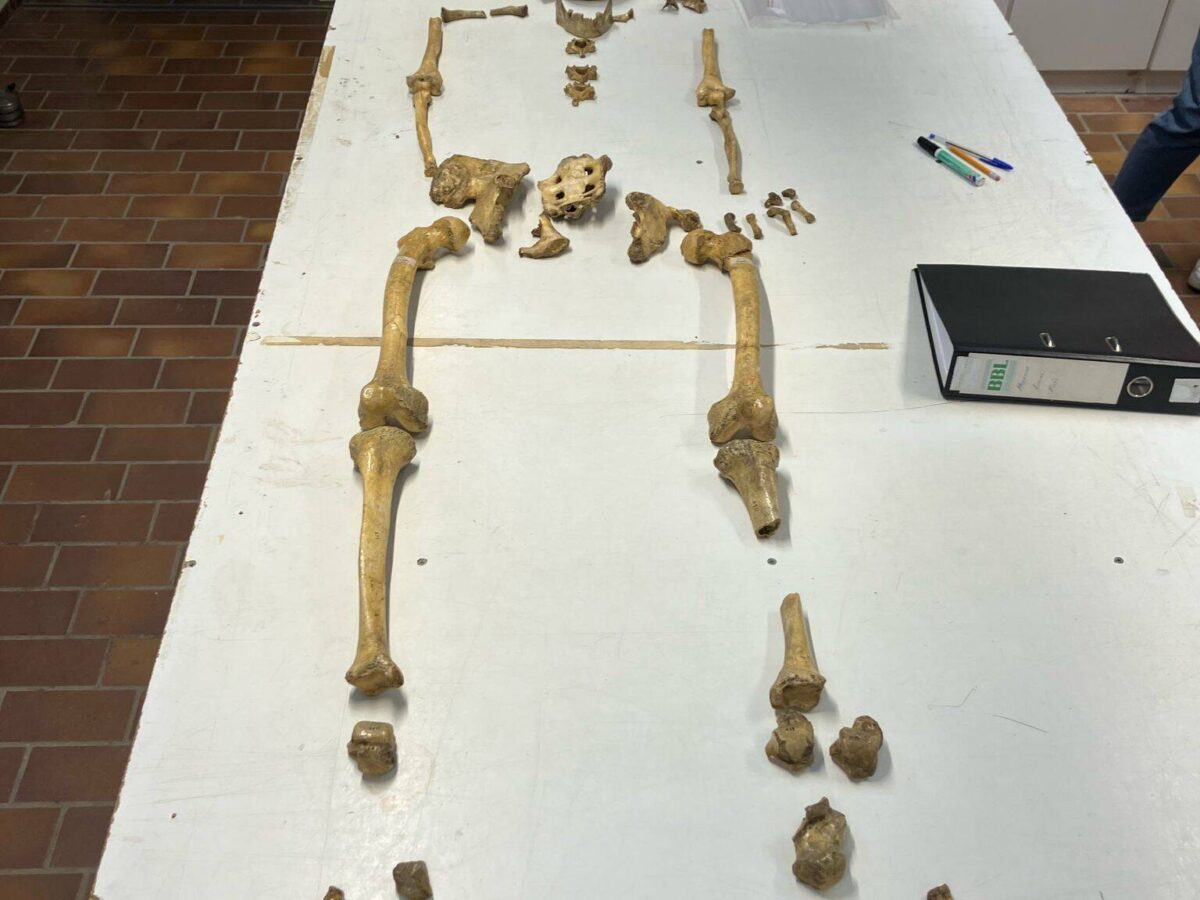

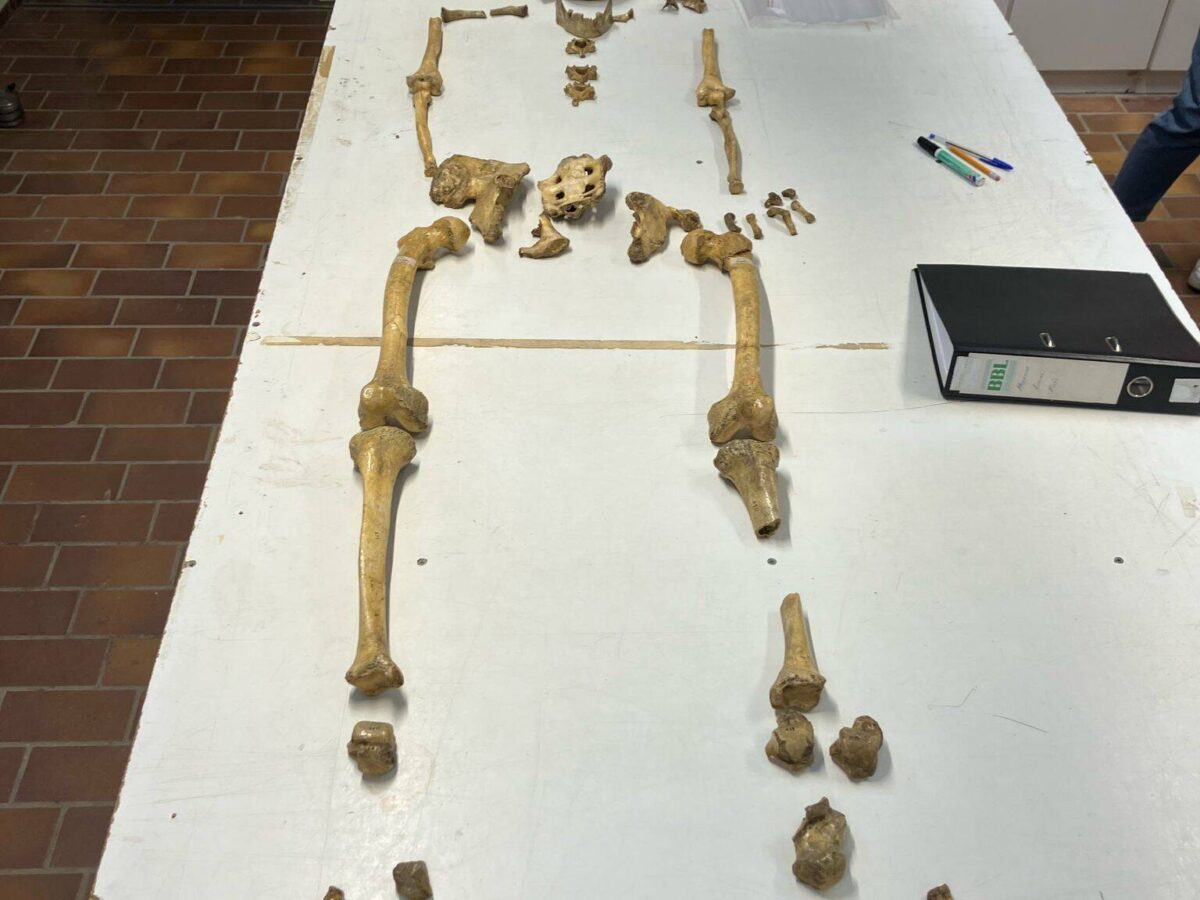

The skeleton was stored in the museum depot and fell into obscurity — apart from a brief mention in a 1946 inventory. In 2024, it was rediscovered during research into burials at Roman villas. The skeleton was selected for scientific study because, given its burial conditions (no covering or grave goods and an unusual posture), it represented a rare example.

Photo: Archaeology in action — the skeleton from Meerssen being examined in 2024 in Belgium. The remains were kept at the Museum of the University of Liège.

Rickets and Arthritis

A team of Belgian and Dutch archaeologists from KU Leuven, Radboud University Nijmegen, VU Amsterdam, and Vrije Universiteit Brussel used a range of techniques including C-14 dating, osteological analysis, and isotope research. Their results revealed that the skeleton belonged to a man aged between 30 and 40 years — who was not in good health. The bones of his legs showed a slight curvature, possibly due to a vitamin D deficiency, an early stage of rickets. One finger appeared deformed by arthritis. These conditions suggest a hard life. The researchers found no traces of violence on the bones, although the skull was damaged — possibly caused by a fall onto the tiled floor between the water basins.

Not from Meerssen

Radiocarbon dating indicated that the man had died between AD 250 and 450. In 1865, Habets had assumed he was a Germanic raider who had died around AD 170. Isotopic analysis provided further insight: although the skeleton was found in Roman Meerssen, the man did not originate from South Limburg. During his life, he seems to have changed diet and moved, suggesting migration. Scientists are now comparing isotope profiles from regions in Germany, the United Kingdom, and Belgium to pinpoint his likely origin. What is clear is that he did not live at the Onderste Herkenberg villa, which had already been abandoned at the time of his death.

A Germanic Raider? Died Around AD 170?— Jozef Habets

Where now

This is only the first phase of research, and archaeologists hope to study more skeletons from across the region. In the fourth and fifth centuries, inhumation burials became common in the northwestern Roman Empire; earlier Romans preferred cremation.

Finds of human remains at several Roman villas suggest that abandoning bodies unburied might have been a ritual way of leaving settlements. Examples of this exist elsewhere in Western Europe, but more research on other villa complexes is needed to confirm this. The exhibition “Roman Villas in Limburg”, organized by the National Museum of Antiquities, the Limburgs Museum, and the Roman Museum, aims to renew interest in sites like Onderste Herkenberg and encourage further study.

Luxury Residence and Farm

Along the Houthemerweg in Meerssen, beneath a large field along the Via Belgica, lie the remains of Villa Onderste Herkenberg — the largest villa rustica ever found in the Netherlands. It was a luxurious residence belonging to wealthy farmers who enjoyed the good life in the Geul Valley.

Remnants of mosaics, painted plaster walls, and underfloor heating testify to a refined interior. A beautiful reconstruction shows the main building with a covered colonnade, timber framing, and gardens with ornamental ponds — a vivid image of Roman comfort in the Dutch landscape.

Illustration: Drawing from the 1865 excavation. The skeleton was found between the two smaller rectangular basins at the bottom of the image.